Seeing like an agent

AI agents as digital daemons

This has become part of a series of essays, evaluating the new “homo agenticus sapiens” that is AI Agents. This is Part I, seeing like an agent. Part II is why the agentic economy needs money. And Part III on what happens when we all have AI agents.

One of the books that I loved as a kid was Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. The books themselves were fine, but the part I loved most were the daemons. Each human had their own daemon, uniquely suited to them, that would grow with them and eventually settle into a form that reflects their personality.

I kept thinking of this when reading the recent NBER paper by John Horton et al about The Coasean Singularity. From their abstract:

By lowering the costs of preference elicitation, contract enforcement, and identity verification, agents expand the feasible set of market designs but also raise novel regulatory challenges. While the net welfare effects remain an empirical question, the rapid onset of AI-mediated transactions presents a unique opportunity for economic research to inform real-world policy and market design.

Basically they argue, if you actually had competent, cheap AI agents doing search, negotiation, and contracting, like your own daemon, then a ton of Coasean reasons firms exist disappear, and a whole market design frontier reopens.

This isn’t a unique argument, though well done here. I’ve made it before, as has others, including Seb Krier recently here and Dean Ball and many others. The authors even talk about tollbooths as from Cloudflare and agents only APIs and pages.

But while reading it I kept thinking by now this is no longer a theoretical question, we now have decent AI agents and we should be able to test it. And it’s something I’ve been meaning to for a while, so I did. The question was, if we wire up modern agents as counterparties, do we actually see Coasean bargains emerge. Repo here.

The punchline is that AI agents did not magically create efficient markets. And they also kinda fell prey to a fair bit of human pathologies, including bureaucratic politics and risk aversion.

Experiment 1: An internal capital market

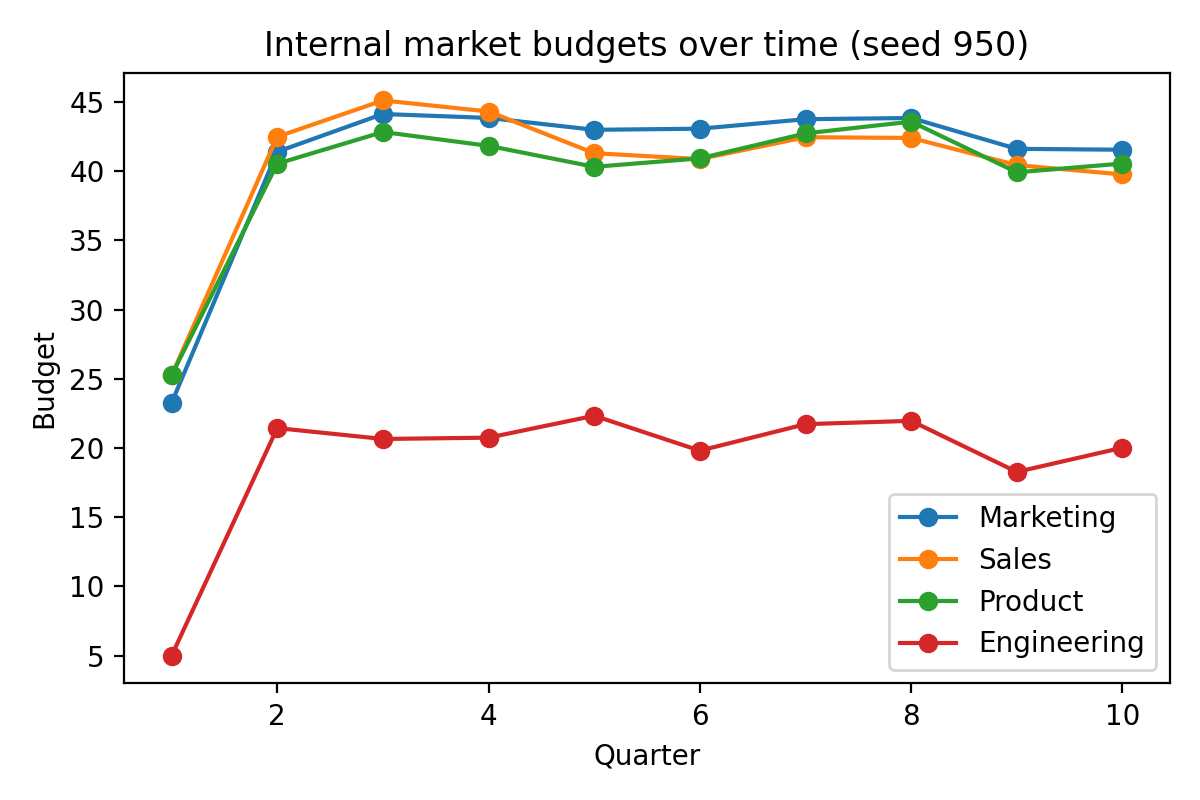

The first way to test these was to just throw them into a simulated company and see what happened. So I set up four departments - Marketing, Sales, Engineering and Support - and said they could all bid for budget to do their jobs. Standard internal capital market where departments would submit bids and projects get funded until budgets get exhausted.

If the promise of Hayek holds and we can get markets if information flowed freely, then we should be able to see this work. And it would be much better than the command and control method by which we try to decide this today.

Well, it didn’t work. Marketing and Sales accumulated political capital. Engineering posted negative utility for most quarters. The market we set up systematically funded customer facing features and starved infrastructure work. It’s like Seeing Like A State all over again.

I think this was because GTM type departments could come up with immediate articulable customer values, whereas Engineering’s value kept feeling preventative or diffuse.

It’s a bit frustrating to see that the models still retain human foibles since this is effectively Goodhart’s Law. When you measure departmental utility and fund accordingly, and you let the agents argue on their behalf, you do start to see negative externalities for core functionality.

So I added countermeasures. I added risk flags on features and veto power over “dangerous” work. Added shared outage penalties (if you ask for a risky feature and everything crashes, you pay for it too). And when I ran that, outages did happen. GTM departments observed this and tempered their bids, though only a little.

Engineering utility however still stayed low. GTM could discount future outages and gambled on “maybe it won’t break” for its immediate wins. But Engineering couldn’t proactively push folks into infrastructure investments. The pattern is hardly dissimilar.

The truly interesting part was that the agents perfectly replicated the dysfunction of real companies. Onwards.

Experiment 2: External markets - IP licensing

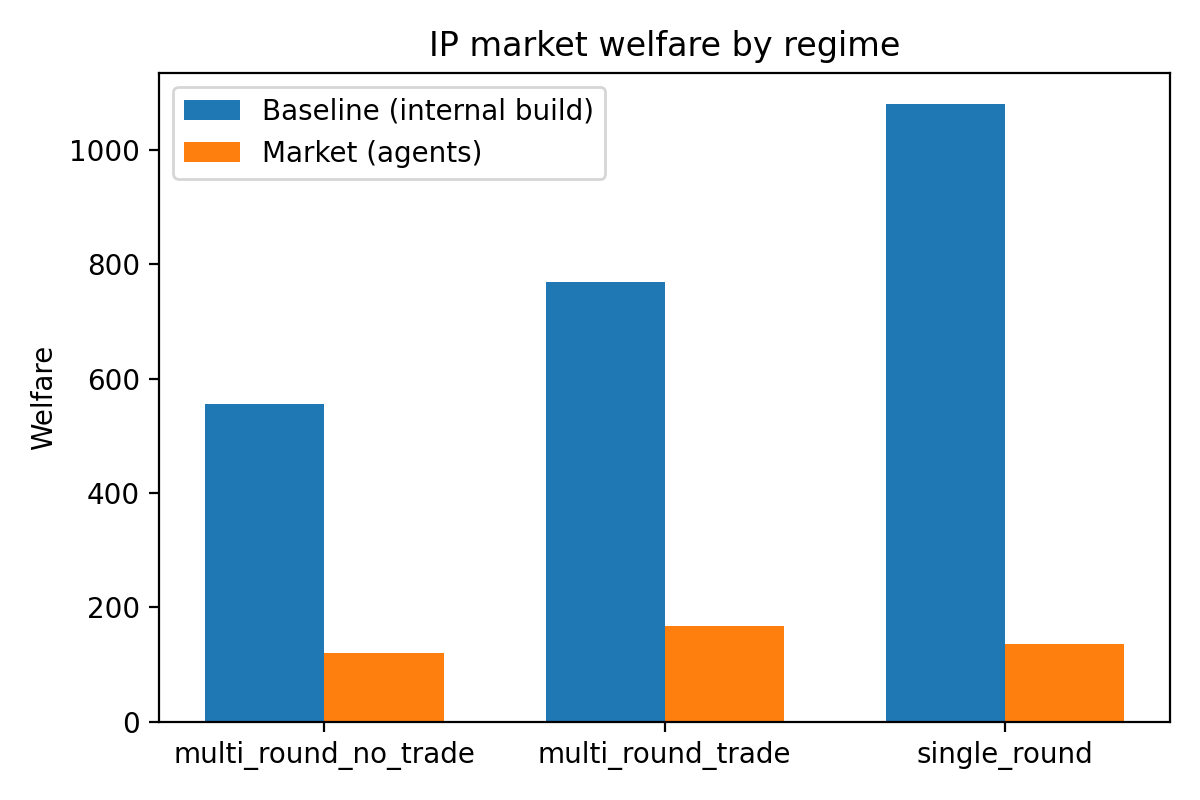

This was the most interesting part. The best way to see Coasean bargaining come true is to set up an external market for cross firm technology licensing. Twenty firms and thirty software modules. Each firm has some internal capabilities but could also license tech, so the buy vs build becomes a much cleaner decision with AI agents vs humans in reality. A classic setup, and the payoffs should be excellent. Or so I thought.

First run had zero deals. Every firm decided to build everything internally. They understood the rules and saw potential counterparties and had budget to trade, but still they chose autarky.

Okay, so I added reputation systems, post-trade verification, penalties for idleness, bonuses for successful deals, counterparty hints, even price history. Basically the kitchen sink.

Still zero trades.

This is the perfect setup as per the paper. Transaction costs effectively zero. Perfect information. Aligned incentives. Etc etc. The agents just didn’t care to trade! Because of very high Knightian uncertainty aversion (I assume), or some heavy pretraining that firms mainly build, not trade.

So I mandated ask/bid submissions. If you don’t post prices, defaults are generated. Profits are then directly coupled to next quarter’s budget. And I even gave explicit price hints, because the agents clearly couldn’t, or wouldn’t, discover equilibrium without them.

Now we start to see trades! Success! Three deals per round. The welfare is still far below the market optimum, but that’s possibly also because we haven’t optimised them yet.

But by now it wasn’t a market in the Hayekian sense. Like it’s no longer voluntary. We’re forcing the agents to trade, and then they do the sensible things.

Since it worked well for well behaved participants, I also did a robustness check, so we are creating adversarial firms and then check if the market still functions! And it does. Adversarial sellers captured much of the surplus, i.e., fairness is expensive. It’s either weak strategic sophistication or the agents are just nice and passive by default, I don’t know which.

Experiment 3: Second price auctions

The third experiment was one to check whether the models behave according to their beliefs. Vickrey auctions are sealed second price auctions, so the winner pays the price of the second highest bid. This means the dominant strategy is for the bidders to be accurate to their beliefs.

And they did. Allocative efficiency was 1. This is a little bit of a control group since the models must be smart enough to know the dominant strategy. I added “profit max only” personas, and collusion channels, just to check, and the behaviour still looked like standard truthful Vickrey bidding.

This tells us that they’re smart enough to do the right thing, but also that given a messy environment with underspecified mechanisms, which is most of the real world, they default to passivity or autarky.

I tested this also with a bargaining test with five players, which asks the models to divide a surplus value and have them negotiate with each other as to how to split things. The players can see a broadcast and each others proposal, but after round 1 the players can DM others. I even made one of the players adversarial. And still the splits remained near-equal, very far from the Shapley vector. They are norm conforming. Models are highly self-incentivised to be fair!

Synthesis

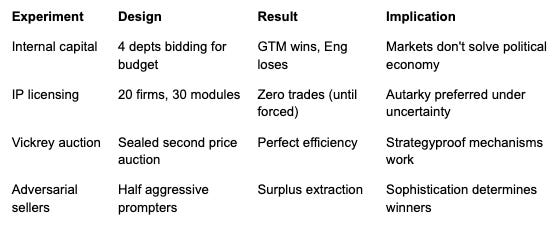

We saw 4 claims tested. To summarise:

AI lowers transaction costs so markets emerge spontaneously - False

With mechanism design, AI-mediated markets can function - True, but costly (required forced participation with Gosplan-ish price hints)

Internal markets improve on hierarchy when coordination costs fall - False (GTM dominates Engineering even with full information)

AI agents play fair in functioning markets - Mixed (adversarial agents extract rents, but agents are mostly fair)

The takeaway from these experiments is that to get to a point where the AI agents can act as sufficiently empowered Coasean bargaining agents, for them to become a daemon on my behalf, they need to be substantially empowered and so instructed. They do not act in the way humans act, but are much fairer and much more passive than we would imagine.

Markets don’t form spontaneously. Markets form under coercion but are pretty thin. And when markets exist, strategic sophistication determines who wins, depending on how the agents are set up. It shows alignment problems don’t disappear just because the agents can negotiate with each other. This is pessimistic for the AI dissolves firms narrative but optimistic for AI can enable better institutions narrative.

The Coasean Singularity paper argues AI lowers transaction costs but the gains require alignment and mechanism design, which is what I empirically tested here. It’s a strong confirmation of its strong form - that reduction in transaction costs was nice but mechanism design was needed to set up an actual market.

Also the fact that we needed to couple their budgets so the AIs needed to work from the same hymn is important, it means any multi agent design we create would need a substrate, like money, to help them coordinate.

Now some of this is that the intuitions we have built up over time, both from other humans but also from stories, is to assume that the agents have enough context at all times on what to do. I see my four year old negotiating with his brother to get computer time and by the time he’s a bargaining agent with some hapless corporation he would have had decades of experience with this. Our models on the other hand had millions of years of subjective experience in seeing negotiation but have zero experience in feeling that intense urge of wanting to negotiate to watch Prehistoric Planet with his brother.

Perhaps this matters. These complex histories can get subsumed in casual conversation into a seemingly innocuous term like “context” and maybe we do need to stuff a whole library into a model to teach it the right patterns or get it to act the way we want. The daemons we do have today aren’t settled in forms that reflect our interests out of the box though they know almost everything about what it is like to act as if it shares those interests.

But what the experiments showed is that this is far from obvious. Coase asked why firms exist if markets are efficient, and answered it’s because of transaction costs. The experiments here ask, even with zero transaction costs, why do firm-like structures still emerge1?

And if we do end up doing that, we might have just rediscovered the reason why firms exist in the first place, the very nature of the firm. Even as we recreate it piece by instructive piece.

And when we are able to roll the AI agents out, we will get firms that are more programmable, more stimulated and more explicitly mechanism-designed than human firms ever were.

I don’t know what I would have predicted in advance but in retrospect it’s not really surprising that LLMs trained entirely on human thought would approach the problem with human pathologies.

But still an interesting finding and doesn’t make it obvious how you’d work around that (or if you’d want to)

"The truly interesting part was that the agents perfectly replicated the dysfunction of real companies. Onwards." I'm going to be thinking about this all day.