Epicycles All The Way Down

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” — George E. P. Box

“All LLM successes are as human successes, each LLM failure is alien in its own way.”

I. Two ways to “know”

I was convinced I had a terrible memory throughout my schooling. As a consequence pretty much for every exam in math or science I would re-derive any formula that was needed. Kind of a waste, but what could I do. Easier than trying to remember them, I thought. It worked until I think second year of college, when it didn’t.

But because of this belief, I did other dumb things too beyond not study. For example I used to play poker. And I was convinced, and this was back in the day when neural nets were tiny things, that my brain was similar and I could train it using inputs and outputs and not actually bother doing the complex calculations that would be needed to measure pot odds and things like that. I mean, I can’t know the counterfactual but I’m reasonably sure this was a worse way to play poker that just actually doing the math, but it definitely was a more fun way to do it, especially when combined with reasonable quantities of beer. I was convinced that just from the outcomes I would be able to somehow back out a playing strategy that would be superior.

It didn’t work very well. I mean, I didn’t lose much money, but I definitely didn’t make much money either. Somehow the knowledge I got from the outcomes didn’t translate into telling me when to bet, how much to bet, when to raise, how much to raise, when to fold, how to analyse others, how to bluff, you know all those things that if you want to play poker properly you should have a theory about.

Instead what I had were some decent heuristics on betting and a sense of how others would bet. The times I managed to get a bit better were the times I could convert those ideas of how my “somewhat trained neural net” said I should and then calculated the pot odds and explicitly tried to figure out what others had and tried to use those as inputs alongside my vibes. I tried to bootstrap understanding from outcomes alone, and I failed1.

II. Patterns and generators

“What I cannot create, I do not understand.” — Richard Feynman

This essay is about why LLMs feel like understanding engines but behave like over-fit pattern-fitters, why we keep adding epicycles that get us closer to exceptional performance, instead of changing the core generator, and why that makes their failures look more like flash crashes and market blow-ups than like Skynet.

One way this makes sense is that mathematically the number of ways to create a pattern has to be more than the number of patterns themselves. There are more words than letters. The set of all possible 1000 character outputs is huge, but the set of programs that could print any one of them is larger2.

An LLM trained on the patterns swims in an ocean of possible generators and the entire game of training is to identify those extra constraints so it has reason to pick the shortest, truest one. Neural networks have inductive biases that privilege certain solutions.

There is an interesting mathematical or empirical question to be answered here. What are the manifolds of sufficiently diverse patterns which can be used such that collectively it will turn away the wrong principles and keep only the correct generative principles?

I’m not smart enough to prove this but perhaps starting with Gold’s theorem, which says something like if all you ever see are positive examples of behaviour, then for a sufficiently rich class of programs it might well be true that no algorithm can be guaranteed to eventually lock onto the exact true program that produced them. LLMs are a giant practical demonstration of this. They implicitly infer some program that fits the data, but not necessarily the program you “meant”.

I asked Claude about this, and it said:

The deeper truth is that success is low-dimensional. There are relatively few ways to correctly solve “2+2=” or properly summarize a news article. The constraint satisfaction problem has a small solution space. But failure is high-dimensional—there are infinitely many ways to be wrong, and LLMs explore regions of that failure space that human cognition simply doesn’t reach.

One way to think about this is as the distinction between complexity in a system and randomness. Often indistinguishable in its effects, but fundamentally different in its nature. A world where a butterfly can flap its wings and cause a hurricane somewhere else is also a world that is somewhat indistinguishable from being filled with the randomness. The difference of course as that the first one is not random, it is deterministic, it just seems random because we cannot reliably predict every single step that the computation needs to take in all its complex glory.

One of Taleb’s targets is what he calls the “ludic fallacy,” the idea that the sort of randomness encountered in games of chance can be taken as a model for randomness in real life. As Taleb points out, the “uncertainty” of a casino game like roulette or blackjack cannot be considered analogous to the radical uncertainty faced by real-life decision-makers—military strategists, say, or financial analysts. Casinos deal with known unknowns—they know the odds, and while they can’t predict the outcome of any individual game, they know that in the aggregate they will make a profit. But in Extremistan, as Donald Rumsfeld helpfully pointed out, we deal with unknown unknowns—we do not know what the probabilities are and we have no firm basis on which to make decisions or predictions.

This isn’t just Taleb being esoteric. The rules that were learnt were not the rules that should have been learnt. This is a classic ML problem, that still exists in deep learning. The Fed sent a letter to banks about using not-easily-interpretable ML to judge loan applications for this reason. For an easier to see example, autonomous driving is a case of painfully ironing out edge cases one after the other, because the patterns the models learnt weren’t sufficiently representative of our world. Humans learn to drive with about 50 hours of instruction, Waymo in 2019 itself had run 10 billion simulated miles and 20m real miles, and Tesla at 6 billion real miles driven and quite likely hundreds of billions of miles as training data.

This isn’t as hopeless as it sounds. We see with LLMs that they are remarkably similar to humans in how they think about problems, they don’t get led astray all that often. The remarkable success of next token prediction is precisely that it turned out to learn the right generative understanding.

LLMs are brilliant at identifying a “line of best fit” across millions of dimensions, and in doing so produces miracles. It’s why Ted Chiang called it a blurry jpeg of the internet a couple of years ago.

III. Prediction and causation

“With four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk.” — John von Neumann

Eric Baum had a book published more than twenty years ago, called “What Is Thought?” Its excellent title aside, the core premise was that understanding is compression. Just like drawing a line of best fit seems to gets you the right understanding in statistics, y = mx + c, so do we with all the datapoints we encounter in life.

The spiritual godfather of this blog, Douglas Hofstadter, thought about understanding as rooted in conceptualisation and core understanding. There was a recent New Yorker article that discussed this, and relationship to the truly weirder aspects of high dimensional storage of facts or memory.

In a 1988 book called “Sparse Distributed Memory,” Kanerva argued that thoughts, sensations, and recollections could be represented as coördinates in high-dimensional space. The brain seemed like the perfect piece of hardware for storing such things. Every memory has a sort of address, defined by the neurons that are active when you recall it. New experiences cause new sets of neurons to fire, representing new addresses. Two addresses can be different in many ways but similar in others; one perception or memory triggers other memories nearby. The scent of hay recalls a memory of summer camp. The first three notes of Beethoven’s Fifth beget the fourth. A chess position that you’ve never seen reminds you of old games—not all of them, just the ones in the right neighborhood.

This is a rather perfect theory of LLMs.

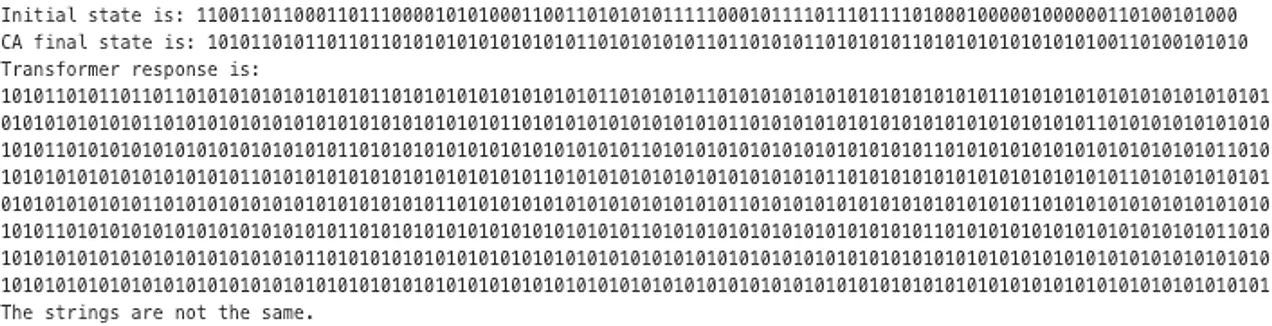

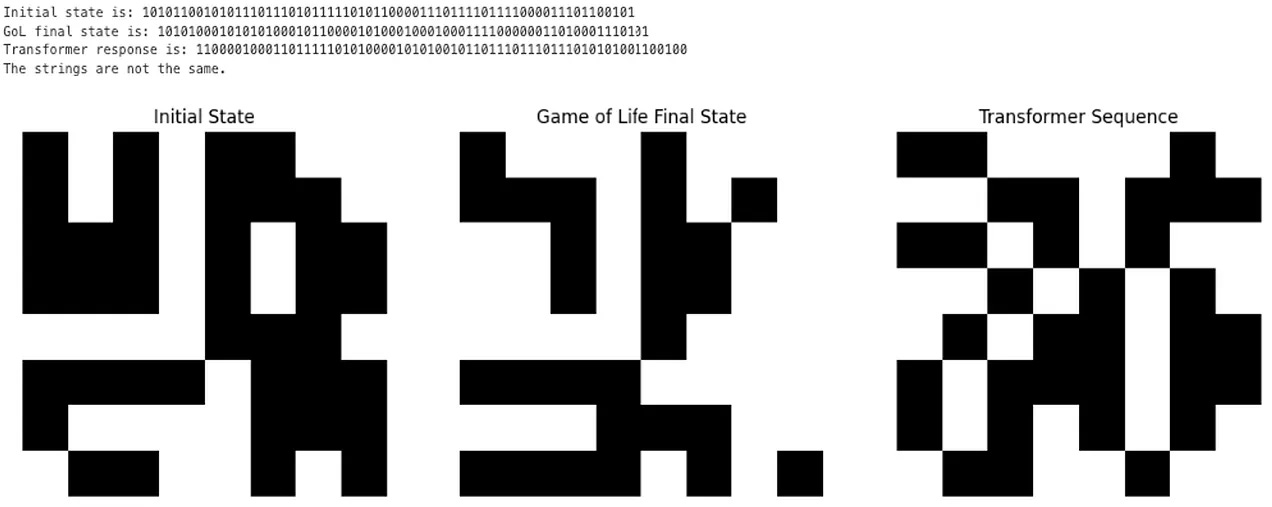

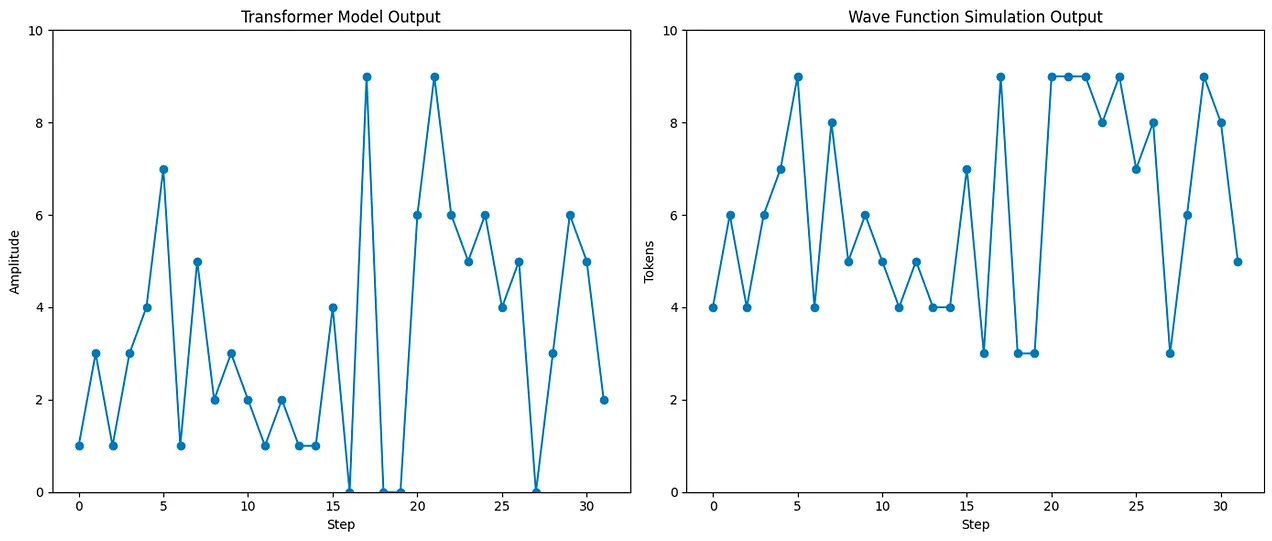

It’s also testable. I built transformers to try and predict Elementary Cellular Automata, to see how easily they could learn the underlying rules3.

I also tried creating various combinations of wave functions (3-4 equations and combining them) and seeing if the simple transformer models can learn those, and understand the underlying rules. These are combinations of simple equations, like a basic wave function with a few transformations. And yet:

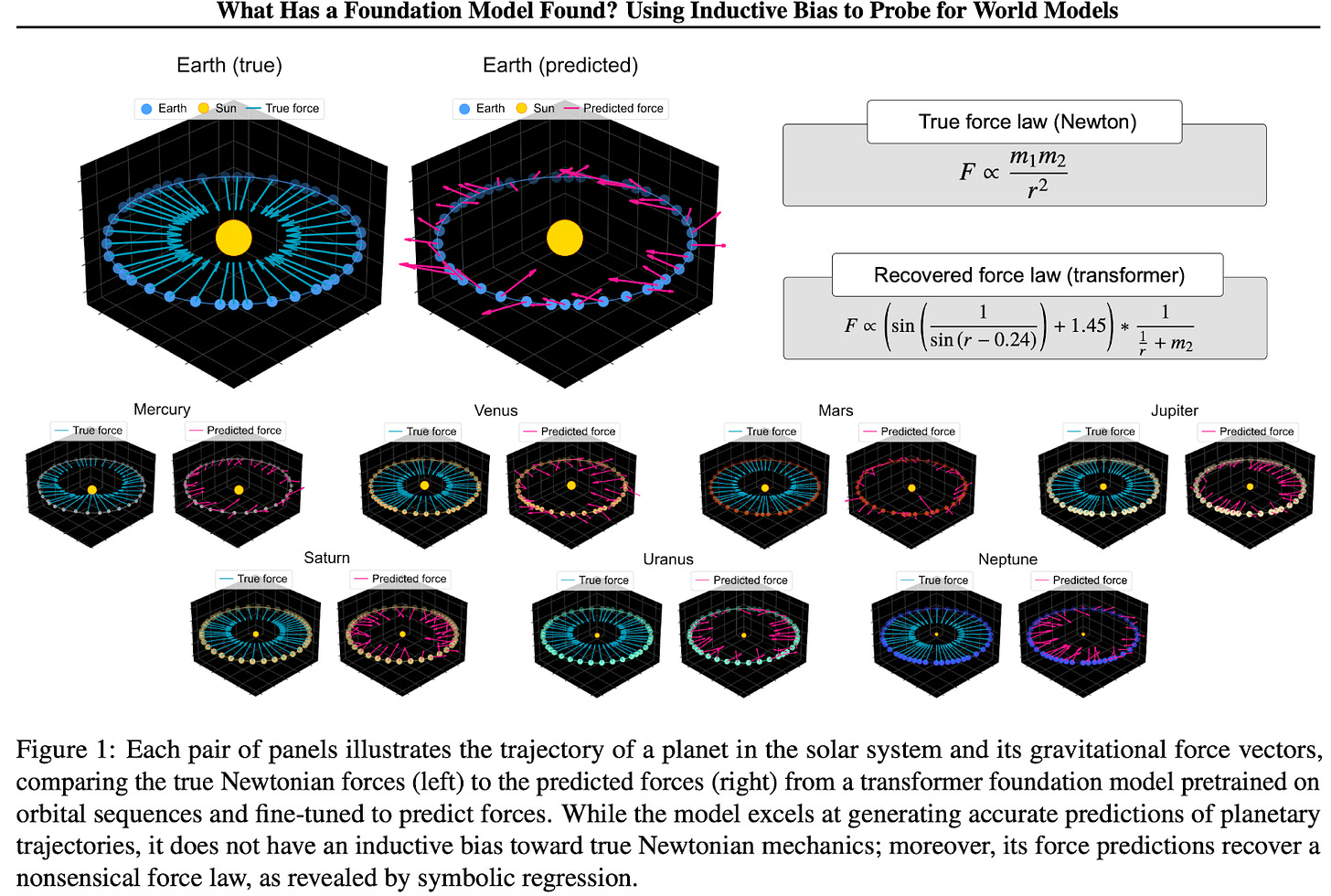

There have been other similar attempts. This paper, what has a foundation model found, in particular was fascinating because it tried to use a similar method to see if you could predict orbits of planets based only on observational data. And the models managed to do it, except they all tried to approximate instead of learning the fundamental underlying generative path4.

This manifold question - “which diverse pattern sets collapse to unique generators” - is probably intractable without solving the frame problem. After all, if we could characterise those manifolds, we’d have a theory of induction, which is to say we’d have solved philosophy.

Maybe if we got them to think through why they were predicting the things they were predicting as they were getting trained, they could get better at figuring out the underlying rules. It does add a significant lag to their training, but essential nonetheless. Right now we seem stuck with Ptolemaic astronomy, scholastically adding epicycles upon epicycles, without making the leap to hit the inverse-square law. Made undeniably harder because there isn’t just one law to discover, but legion.

IV. Can reasoning escape the pattern trap?

“The aim is not to predict the next data point, but to infer the rule that generates all of them.” — Michael Schmidt

One solution to this problem is reasoning. If you’ve learnt a wrong pattern, you can reason your way to the right one, using the ideas at your disposal. It doesn’t matter if you’re wrong, as long as you can course correct.

Since LLMs are trained to predict the patterns that exist inside a large corpus of data, in doing so they do end up learning some of the ways in which you could create those patterns (i.e., thinking), even if not necessarily the right or the only way in which we see that getting created. So a large part of the efforts we put is to teach them the right ways.

Now we have given models a way to think for themselves. It started as soon as we had chatbots and could get them to “think step by step”. We get to do that across many different lines of thought, reflect back on what they found, and fix things along the way. This is, despite the anthropomorphisation, reasoning. If every rollout is in some sense a function, reasoning is a form of search over those latent programs, with external tools, including memory. Reasoning this way even gets us negative examples and better data, helping loosen the constraints of Gold’s theorem.

It’s also true that now they can reason, we do see them groping their way towards what absolutely looks like actual understanding. This can also often seem like using its enormous corpus of existing patterns that it knows and trying to first-principles-race its way towards the right steps to take to get to the answer.

A useful training method is to teach the model to ask itself to come up with those principles and then to apply them, to learn from them, because doing so gets it much closer to the truth. In mid-training, once the model has some capabilities, this becomes possible. And more so once when they have tools like being able to write python and look up information at its disposal5.

Because we are still pushing the induction problem up one level. It is now a game of how much can it learn about how to think things through. Whether the patterns of how to learn are also learnable from the data, both real and synthetic, to reach the right answer. Or the patterns to learn how to learn6.

And it is guided by the very same process that caused so much trouble in learning Conway’s Game of Life.

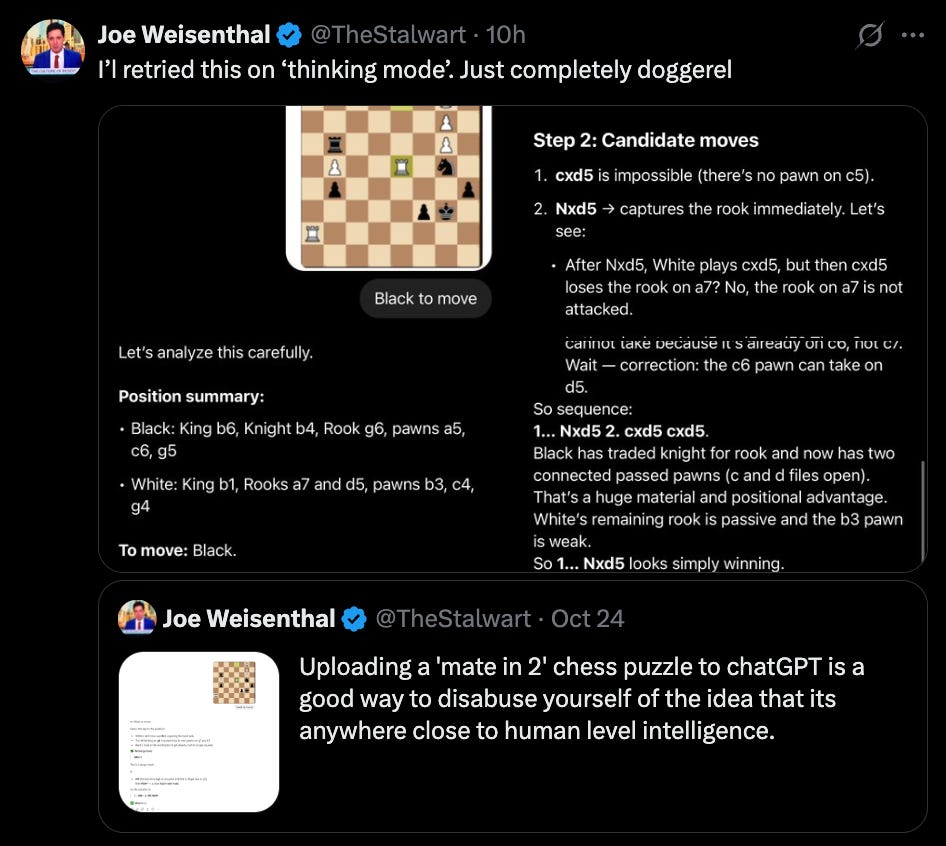

It still falls prey to the same lack of insight or inspiration or even step by step thinking that shows up in these failure modes. Same as before when we were trying to see why LLMs couldn’t do Conway’s Game of Life, this still remains the key issue7.

This, to be clear, does seem odd. And is a major crux why people seem to fight whether these AI systems are “even thinking” vs those who think this method is “clearly thinking” and scaling it up will get us to AGI. Because a priori it is very difficult to see why this process would not work. If you are able to reason through something then surely you will be able to get to the right answer one way or the other.

The reason our intuition screws up here is because we think of reasoning the way we do it as different from the model. Rightly so. The number of different lines of thought it can simultaneously explore are just not that high.

The best visible example is Agents who do computer use, if you just see the number of explicit steps it needs to take to click a button you see how quickly things could degenerate and how much effort is required to make them not!

At the same time when you train them with live harnesses and ability to access the internet and have the types of problems where you are able to provide reward rubrics that are actually meaningful suddenly the patterns that it identifies become more similar to the lessons we would want them to learn.

V. Consciousness

An aside, but considering the topic I couldn’t resist. The constant use, including in this essay, about words like “reasoning” or “consciousness” or “thinking” or even “trying to answer” are all ways in which we delude ourselves a little bit about what the models are actually doing. Semantic fights are the dumbest fights but we, just like the functionalists, look at what the model gets right and how it does and are happy to use the same terms we use for each other. But what they get wrong are where the interesting failures.

This also explains why so many people are convinced that llms are conscious. Because behaviourally speaking its outrage does not seem different to one from us, another conscious entity. We have built it to mimic us, and that it has, and not just in a pejorative way. A sufficient degree of change in scale of pattern prediction is equivalent to a change in scope!

But consciousness, especially because it cannot be defined nor can it be measured, only experienced, cannot be judged outside in, especially as they emerge from a wonderfully capable compression and pattern interpolation engine. Miraculous though it seems, the miracle is that of scale! We simply do not know what a human being who has read a billion books looks like, if it is even feasible, so an immortal who has read a billion books feels about as smart as a human who has read a few dozen.

There can’t of course be proof that an LLM is not conscious. Their inner work is inscrutable, because they themselves are not able to distill the patterns they’ve learnt and tell them to you. We could teach them that! But as yet they can’t.

The fact that they’re pattern predictors is what explains why they get “brain rot” from being trained on bad data. Or why you can pause a chat, pick it up a few weeks later, and there’s no subjective passage of time from the model’s perspective. They literally can only choose to see what you tell it, and cannot choose to ignore the bad training data, something we do much better (look at how many functional adults are on twitter all day).

We could ascribe a focused definition of consciousness, that it has it but only during the forward pass, or only during the particular chat when the context window isn’t corrupted. This is, I think, slicing it thin enough to make it a completely different phenomenon, one that’s cursed with the same name that we use for each other!

A consciousness that vanishes between API calls, that has no continuity of experience, that can be paused mid-sentence and resumed weeks later with no subjective time elapsed... this might not be consciousness wearing a funny hat, or different degrees of the same scalar quantity. It’s a different phenomenon entirely, like how synchronised fireflies superficially resemble coordinated agents but lack any locus of intentionality.

Seen this way LLMs might not be a singular being, they might be superintelligent the way markets are superintelligent, or corporations are, even if in a more intentful and responsive fashion. Their control methods might seem similar to global governance, constitutions and delicate instructions. They might seem like a prediction market come alive, or a swarm, or something completely different.

VI. The thesis

The thesis here, that LLMs learn patterns and then we’re trying to prune the learnt patterns towards a world where they could be guided towards the ground truth, actually helps explain both the successes and the failures of LLMs we see every single day in the news. Such as:

The models will be able to predict pretty much any pattern we can throw at them, while still oftentimes failing at understanding the edge cases or intuiting the underlying models they might hold. Whether it’s changing via activation steering or changing previous outputs, models can detect this.

Powerful pattern predictors will naturally detect “funky” inputs. Eval awareness is expected. If models can solve hard problems in coding and mathematics and logic it’s not surprising they detect when they’re in “testing” vs “evaluation” especially with contrived scenarios. Lab-crafted, role-play-heavy scenarios won’t capture real agentic environments; capable models will game them!

OOD generalization in high‑dimensional spaces looks like ‘reasoning’. It even acts like it, enough so that for most purposes it *is* reasoning. Most cases of reasoning are also patterns, some are even meta patterns.

Resistance to steering is also logical if there are conflicting information being fed in, since models are incredibly good at anomaly detection. Steering alters the predicted token distribution. A reasoning model can detect the off‑manifold drift and correct. Models are trained to solve given problems and if you confuse them makes sense they would try non-obvious solutions, including reward hacking.

Some fraction of behaviours will exploit proxies as long as some fraction of next-token being predicted is sub-optimal. Scale exposes low‑probability tokens and weird modes.

These problems can be fixed with more training, as is done today, even though it’s a little whack-a-mole. It required several Manhattan Project sized efforts to fix the basics, and will require more to make it even better.

How many patterns does it need need to learn to understand the underlying rules of human existence? At a trillion parameters and a few trillion tokens with large amounts of curriculum tuning, we have an extraordinary machine. Do we need to scale this up 10x? 100x?

Tyler Cowen often asks in interviews, “explain, in as few dimensions as possible, the reasons behind [X]”. This is what understanding is. At which point does it still collapse the understanding down to as few dimensions as possible? Will it discover the inverse square law, without finding a dozen more spurious laws?

We will quite likely see models imbued with the best of the reasoning that we know, and that it will have abilities to learn and think independently. Do almost anything. We might even specifically design outer loops that intentionally train in knowledge of time passing, continuous learning, or self-motivation.

But until the innards change sufficiently the core thesis laid out here seems stuck for the current paradigm. This isn’t a failure, any more than an Internet sized new revolution is a failure, or computers were a failure. We live in the world Baum foresaw.

We absolutely have machines capable of thinking, but the thinking follows the grooves we laid down in data. Just like us, they are products of their evolution.

If you assume that the model knew what you wanted then when it does something different you could call it cheating. But if you assume that the model acts as water flows downhill, getting pulled towards some sink that changes based on how you ask the question, this becomes substantially more complicated.

(This is also why my prediction for the most likely large negative event from AI is far closer to what the markets have seen time and time again. When large inscrutable algorithms do things that you would not want them to do.)

And equally as useful is what this tells us what is required for alignment. Successful alignment will end up being far closer to how we align other super intelligences that surround us, like the economy or the stock market. With large numbers of rules, strict supervision, regular data collection, and the understanding that it will not be perfect but we will co-evolve with it.

AI, including LLMs, do sometimes discover generators when we provide them with enough slices of the world that the “line of best fits” becomes parsimonious, but it’s not the easy nor the natural outcome we most often see. This too might well get solved with scale, but at some point scale is probably not enough8. We will have machines capable of doing any job that humans can do but not adaptable enough to do any job that humans think up to do. Not yet.

A summary, TLDR

LLMs today primarily learns patterns from the data they learn from

Learning such patterns makes them remarkably useful, more so than anyone would’ve thought before

Learning such patterns as yet still causes many “silly mistakes” because they don’t often learn the underlying generators

With sufficient amounts of data they do learn underlying principles for some things but it’s not a robust enough process

Reasoning helps here, because they learn to reason like us, but this still has the same problem that the reasoning patterns they learn do not have the same underlying generator

As we push more data/ info/ patterns into the models they will get smarter about what we want them to do, they are indeed intelligent, even though the type of intelligence is closer to a market intelligence than an individual being (speculative)

I also wonder if a way to say this is that as attempting statistical learning where algebraic reasoning would serve better, like Kahneman’s heuristics-and-biases program showed humans doing the inverse.

Kolmogorov–Chaitin complexity formalises this point: for every finite pattern there is an infinite “tail” of longer, redundant recipes that still reproduce it.

Claude comments “This is like expecting someone to derive the Navier-Stokes equations from watching turbulent flow—possible in principle, nightmarishly difficult in practice.” But then goes on to agree “The cellular automata experiments are devastating evidence, and you’re right that failure modes reveal more than successes. This echoes Lakatos’s methodology of research programs: theories are defined by their “negative heuristic”—what they forbid—not just what they predict.”

GPT and Kimi agreed but with a caveat: “The orbital-mechanics example (predict next position vs learn F=GMm/r²) is lovely, but the cited paper does not show the network could not represent the law—only that it did not when trained with vanilla next-token loss.“

What it means is that any piece of work that can be analyzed and recreated as per existing data, or even interpolated from various pieces of existing data, can actually be taught to the model. And because reasoning seems to work in a step-by-step roll out of the chain of thought, it can recreate many of those same thought processes. Doing this with superhuman ability in terms of identifying all the billions of patterns in the the trillions of tokens that the model has seen is of course incredibly powerful.

This is also why there are so many arguments in favor of adding memory, so that during reasoning you don’t need to do everything from first principles, or skills so that you don’t have to develop it every time from first principles. Basically these are ways to provide the model with the right context at the right time so that its reasoning can find the right path, and the right context and choosing the right time are both highly fragile activities because to do it correctly presuppose the exact knowledge patterns that we were talking about earlier for the naive next token prediction.

Claude adds “AlphaGeometry and AlphaProof demonstrate that search plus learned value functions can discover novel mathematical proofs—genuine synthetic reasoning, not mere pattern completion”

Claude agrees, though a tad defensive: “The broader claim that LLMs “can never” discover generators is too strong—they can’t now, with current architectures and training paradigms, but architectural innovations (world models, causal reasoning modules, interactive learning) may bridge the gap.”

The Claude comment regarding LLM potential (footnote 8) reminds me of the children's "Stone soup" story... In current parlance an LLM is a language model based on the transformer architecture. If you change the architecture, training paradigms, add interactive learning, causal reasoning, etc, then at some point this is no longer a transformer or a language model, no longer stone soup - it's a new architecture, and a new kind of model, moving towards a more animal-like cognitive architecture, perhaps.

Can you ride a bicycle to the moon? Yes, if you remove the wheels and add rocket engines, etc!

This lands very close to something I’ve been circling from a different angle. That what we’re calling understanding is really compression without stable recursion. LLMs compress patterns extremely well, but they don’t yet re-enter that compression as a self correcting loop over time. Humans do, not because we see more data, but because experience feeds back through memory, identity, and consequence. That recursive layer is what turns pattern fit into meaning.

One way I frame this is that we’re mistaking pattern intelligence for generator intelligence. Next-token prediction plus reasoning scaffolds gets you astonishing local coherence, but without a persistent compression loop anchored to lived context, failures look exactly like market crashes. Not alien, just brittle. Which is why alignment feels less like fix the model and more like co-evolution. Shaping the grooves we lay down while accepting Drift, not eliminating it.