The Tragedy of the Agentic Commons

Eliciting preferences using AI improves matches, but everyone getting their own agent will still necessitate markets

Written with Alex, who writes here, and you should read him! The repo here.

This has become part of a series of essays, evaluating the new “homo agenticus sapiens” that is AI Agents. Part I was seeing like an agent. Part II is why the agentic economy needs money. And this is Part III.

Whitney Wolfe Herd, Bumble’s founder, recently described a future where your AI chats with potential matches’ AIs to find compatibility. Say what you will about AI being involved in your love life, but this is one domain where AI agents can potentially have large returns: the dating/marriage “market” is the epitome of the type of high-dimensional matching problem that Herbert Simon identified as impossible for people to optimize. Rather than optimising, Simon argued people engage in “satisficing”, i.e., settling for good enough.

Why would AI agents be useful here? Let’s start with how most markets work. Hayek’s big insight–outlined in what he called the economic problem of society–was that prices do an incredible amount of work. They compress a ton of information such as preferences, costs, scarcity, expectations into a single number that acts as a sufficient statistic for value. When you’re buying oranges, the seller doesn’t care what you’ll do with them. The price coordinates the transaction and that’s enough.

But prices work best when the transactions involve commodities. When you’re buying some oranges, the seller doesn’t particularly care what you’re going to do with them; you don’t need to convince him that you’ll take care of the fruit. The price does all the work in coordinating that transaction. Matching markets are conceptually different. You can’t just choose your spouse, your employer, or your college: you also have to be chosen by them. This is the domain that Al Roth, the 2012 Nobel winner for “the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design,” spent most of his career studying. Roth showed that matching markets require careful institutional design; this design includes algorithms, timing, and the right rules to get the market to “clear.” His deferred-acceptance mechanisms now allocate medical residents to hospitals, students to schools, and kidneys to patients.

But the efficiency of matching markets hangs on the ability to elicit a person’s preferences, i.e., that people can express their rank orderings over potential options. But what if people’s preferences don’t fit in dropdown menus or are difficult to articulate on a standardised questionnaire? Peng Shi studied in his excellent paper “Optimal Matchmaking Strategy in Two-Sided Markets.” He looks at online platforms that match customers to providers using a variety of matchmaking strategies, from searching one side of the market to centralised matching that allows for back-and-forth communication.

Shi found that centralised matching works beautifully when preferences are “easy to describe,” i.e., straightforward to elicit using standard questionnaires, but breaks down when they’re contextual, idiosyncratic, or otherwise difficult to express through standard techniques. This is why many platforms still make you search. You want a contractor who shows up on time and knows your budget–this is easy–but you also want someone who understands your tastes in postmodern living room design. Good luck expressing that on a dropdown web form.

Here is where Large Language Models come in. They are fantastic at turning any unstructured piece of information into better structured matching. They’re also eminently scalable, enabling Coasean bargaining. But scaling things brings with it more coordination problems, too many agents negotiating with too many other agents is noisy. So what type of an institutional setup would make most sense to install here, to make this work well?

That’s what we sought to test with our experiments. The question being, could we figure out how and whether LLMs can help in matching markets where preferences are “hard to describe”? Can LLMs actually elicit the dispersed, hard-to-articulate preferences better than standardised methods? And if they can, what happens when LLM-based agents are available to everyone in the market?

Now, there’s some recent work on the topic that suggests guarded optimism that this is possible. Very new work by Ben Manning, Gili Rusak, and John Horton show that, when parsed through LLMs, short natural-language “taste descriptions” can be superior to standard questionnaires for eliciting preferences when the option set is large. They run an experiment where people write a few paragraphs about what they want in a job and then rank between 10 and 100 options (depending on the condition). Consistent with Simon’s conjecture, people’s ranking effort plateaus as the option size grows large; choice quality grows unstable as the consideration set increases. People get tired of ranking a ton of options and just start guessing. AI-parsed “taste descriptions” scale much better: once tastes are written down, the marginal cost of evaluating one more option is negligible for an AI agent. The advantages of AI-parsed matches are even higher in congested markets where people are more likely to be pushed.

But a theoretical paper by Annie Liang offers an important counterpoint in the case of a potentially complex two-sided matching market. She shows that when personality is sufficiently high-dimensional, meeting just two people in person beats searching over infinitely many AI representations. The noise in AI approximations compounds faster than the benefits of scale. This is a very cool result, and you should all read the paper in full–it’s that perfect type of economic theory that’s both conceptually rich and practically useful.

Ok, with that preamble…

Let’s run an experiment

We set up a simulated Hayekian marketplace with a whole bunch of digital shoppers, providers as AI agents.

Preference elicitation: Knowledge is dispersed in each digital shopper’s “head”: customers know what they want and providers know what they can offer. We want to know how eliciting the preference–either through the standard intake questionnaire or high-dimensional text parsed by an AI agent–can change the market structure for optimal results.

Mechanism interaction: When elicitation improves, can centralised matching beat search, and what are the conditions under which this happens?

Scale: We then check what happens when everyone uses AI agents

Institutional design: Finally, we figure out the right institutional mechanism to solve the resulting problems, and to maximise welfare

Preferences here are latent vectors in each agent’s head. Both the customer and provider agents have a true weight vector over some set of attributes (6 dimensions in this case). So elicitation changes the platform’s inferred w, not the true w. A standard intake is a structured form, and only exposes a few coarse priorities. The AI intake is free text, back-and-forth chat, and can be parsed in the platform’s inferred weight by a couple mechanisms - either by a rule- based algorithm or an AI agent.itself or , or via GPT parsing.

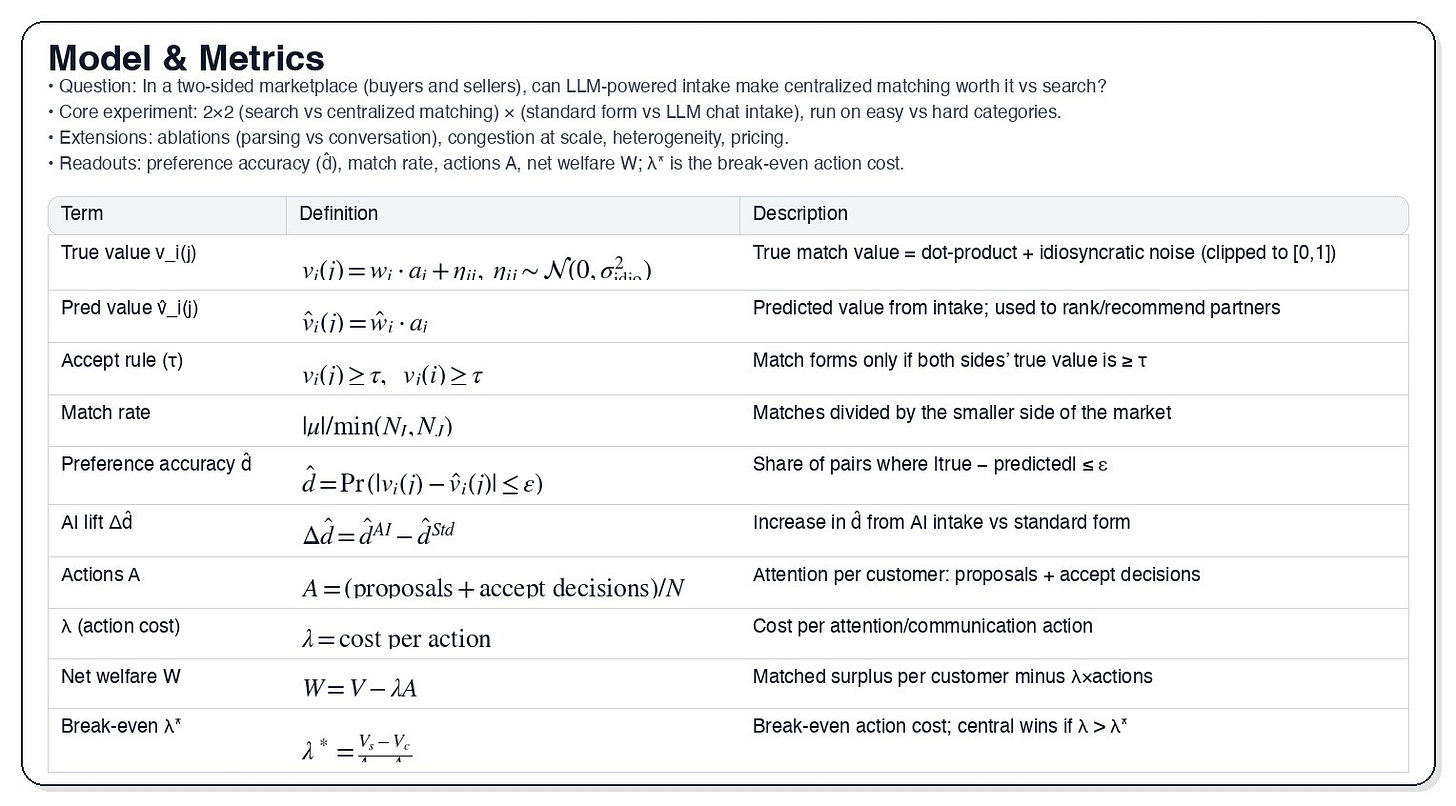

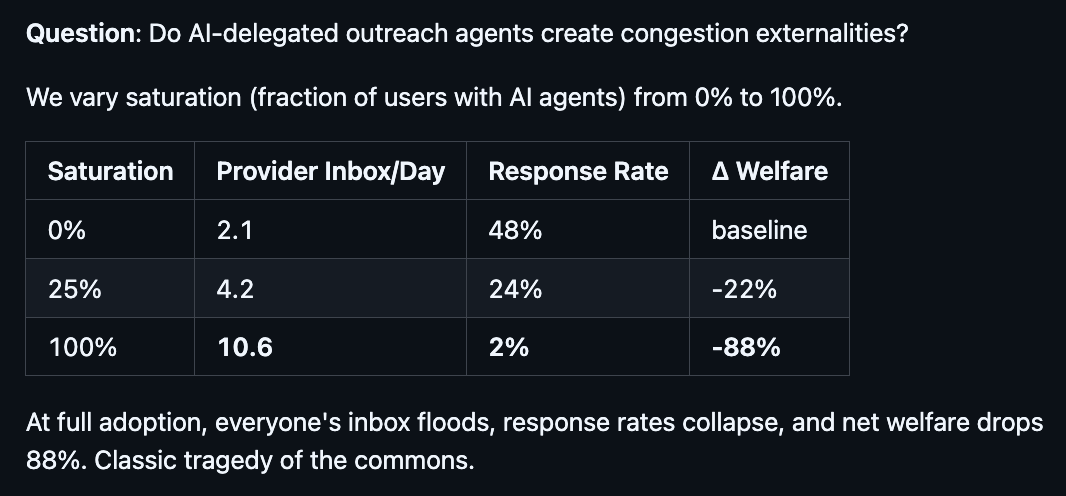

Figure 1 has an abridged illustration of the design and some results. There’s an appendix at the end of the essay in case you want to check out the details of the experimental design. But without further ado, here are some…

Results

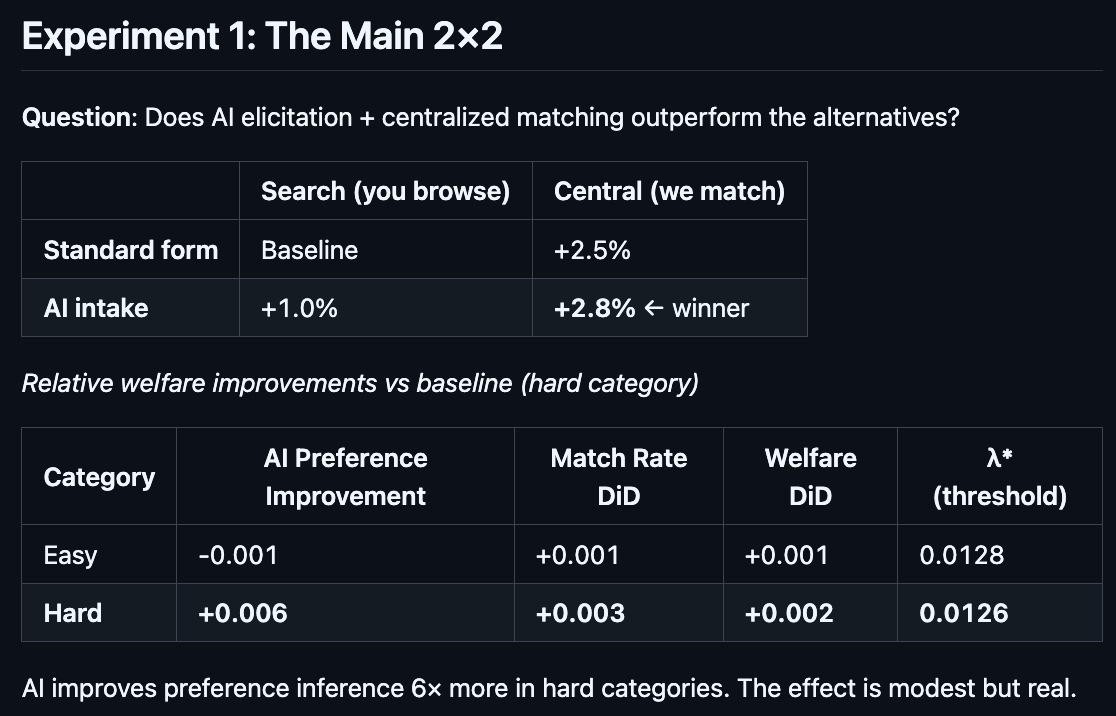

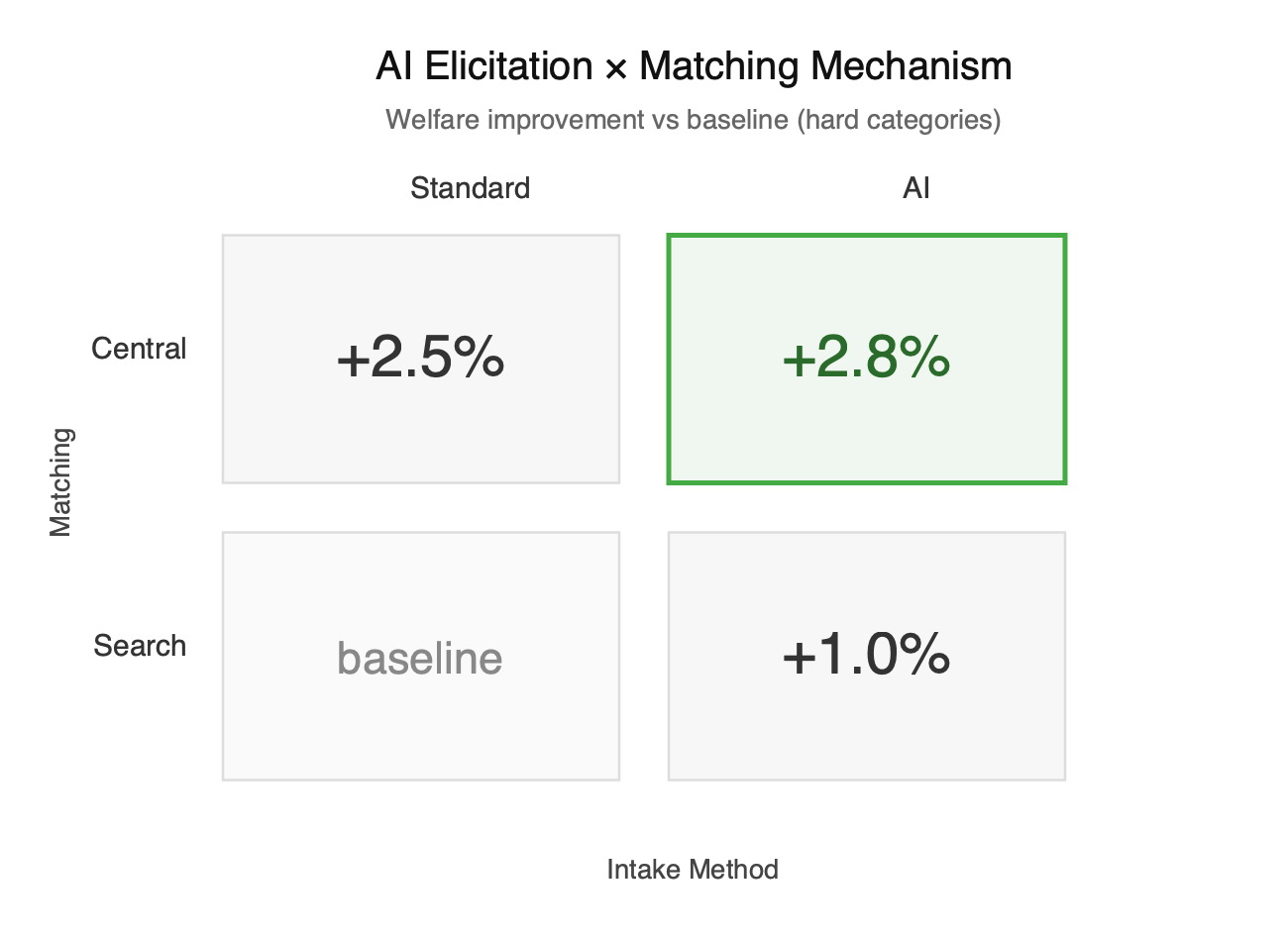

First, AI-assisted preference elicitation improves matches across the board.

Figure 1: Experimental design

Figure 2

Second, as shown in Figure 2, AI-based elicitation changes what type of market design works best, and the conditions under which centralised matching can beat search.

Specifically, “Search” and “centralised” are the two different matching protocols we tested. Search means customers iteratively message providers in some ranked order until the matches ‘stick’. Think about how you would find a plumber–message folks, talk to them, iteratively until one ‘fits’.

Centralised is where the platform computes the shortlist for you, and clears a match based on mutually acceptable terms.

Once dispersed knowledge can be elicited and compressed into usable signals, the platform can centrally clear the market rather than forcing users to search. When knowledge can’t be compressed, search dominates because it lets users do iterative, contextual refinement in the loop.

The core object is the ‘ROI boundary’. If the per action attention cost is high enough, centralisation dominates–it just requires fewer actions. If the cost is low, search can dominate because it can “handle” more actions. This is the very idea of Coasean bargaining helping remove the boundaries of firms.

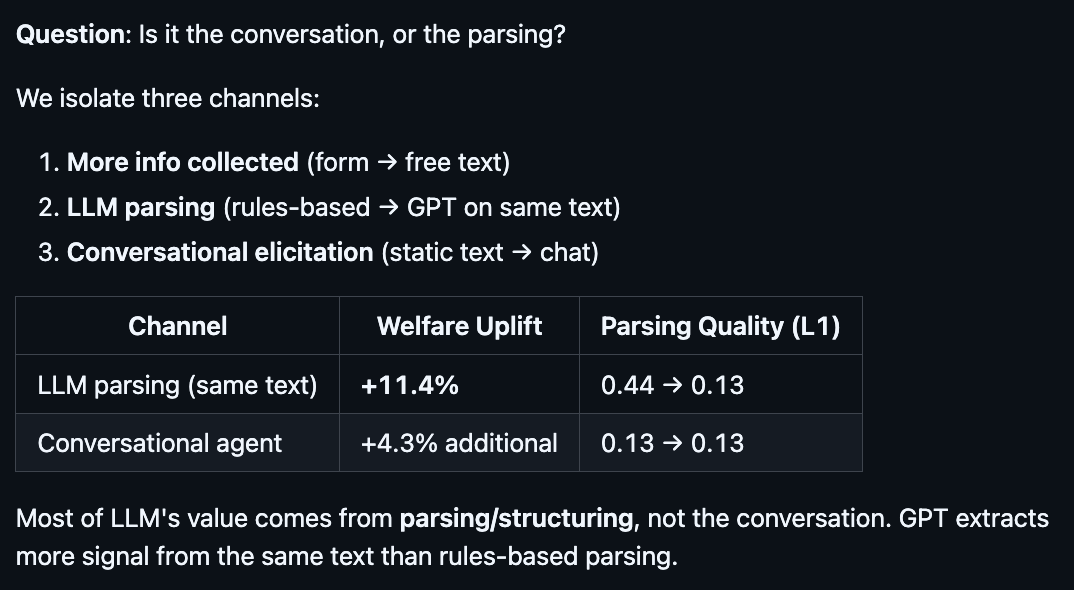

So where does the value of LLM-based elicitation actually come from? Is it from the back and forth conversation, or the ability to parse large text? As described above, we prompted all of the customers to write some free text about things they like and whatnot, and then used some rules-based parsers and some LLM-based parsers. There’s also the option for conversational elicitation via chat.

We thought the AI agents’ ability to ask follow-up questions would be the game-changer. Turns out though (see Figure 3), most of the value comes from the AI agent simply inferring more signal from messy text compared to the signal in a rule-based parser. This is consistent with the work of Manning et al. that we discussed above. This may of course be something specific to our prompts—perhaps one could obtain further gains by explicitly instructing the AI agents to engage in structured back-and-forth with the customers, and to do so in contexts where this would be helpful, but this was not the case here.

This highlights the utility of LLMs for extracting (potentially high dimensional) signals from unstructured data. Back in the day OKCupid used to make people fill out 90-100 questions to help match them with their potential partners. With LLMs, they might’ve been able to get away with writing a short essay and getting their Agentic Cupid to pull out the relevant information. Whitney is certainly on to something.

Figure 3

But what if people don’t really know what they want, does preference uncertainty matter? Whenever Rohit shops, he’s not sure of what he wants before he goes in the store. There’s a lot of noise in the process. Alex is a pure satisficer: the first item that meets a (very low) threshold gets put in the cart (usually virtual), and off to check out he goes.

We can test for that pretty easily here by introducing a bit of randomness into our shoppers’’ heads. At least in our setting, injecting noise into preferences doesn’t matter for the AI’s ROI all that much. We can still do centralised matching and extract a lot of value from that mechanism—as long as the preference noise isn’t too cacophonous.

What if everyone uses an LLM agent?

We had originally set up a pretty small marketplace. The centralized mechanism at this scale can be computed and cleared so we can run the experiment. But what happens when the scale explodes, both in the number of options and the number of customers potentially using AI agents? This is the problem matching platforms like Upwork are trying to solve: the option set is absolutely huge, but so is the potential customer base.

Every time a customer opens up a marketplace like Upwork, the number of choices just on the front page makes it hard to remember what they came for. Ideally AI-delegated agents can solve this problem: the user speaks or writes down what they want to do, the AI agent pings the platform, and the user is presented with the match. But what if every potential shopper had their own AI agent who wanted to message the providers on the platform? That’s a lot of agents doing individualised message sending to the provider inboxes!

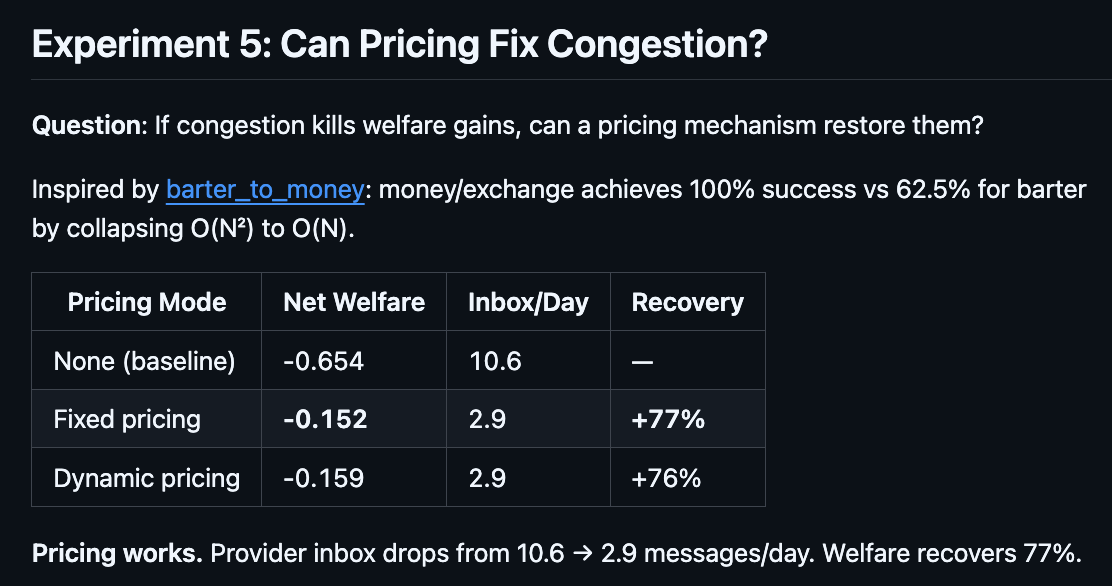

So as you increase the number of customers with AI agents, the level of congestion rises significantly. Each customer agent sends a query to a provider agent’s inbox and it has to respond. Responding to all those agents takes a lot of compute. Here is what happens in our simulation (Figure 4): At full adoption, the providers’ inboxes flood with 5x the amount of requests, response rates collapse from 48% to 2%, and net welfare drops 88%.

Figure 4

Without institutions in place to scaffold the marketplace, a tragedy of the commons emerges: If everyone has an AI agent, it’s almost like nobody does. The paradox of plenty is real, and AI agents create their own version of Jevons paradox.

The need for institutions and scaffolding

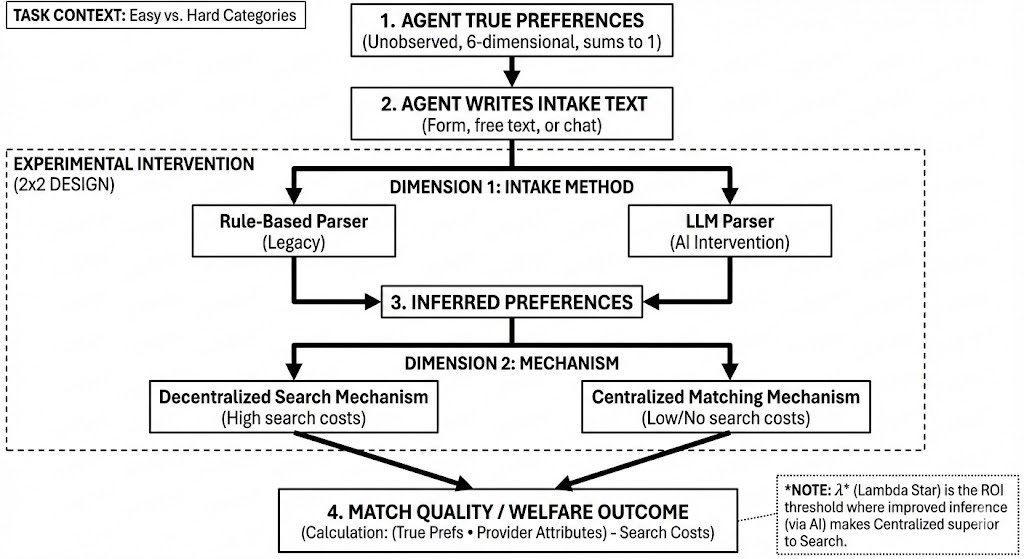

What can fix this type of congestion? Prices!

As in a previous post–where we showed the importance of money in coordinating trade amongst AI agents–introducing a price mechanism recovers most of the lost welfare in matching. A vindication of Hayek’s deeper insight.

Specifically, we can introduce an exchange and money, such that the agents now have a pricing mechanism to signal their “strength of preference”. The idea is that the complexity falls because now not every provider and customer need to message each other. Prices capture a lot of high dimensional information in a single statistic, streamline a lot of that information, as we’d seen with the simulation in as we saw in the simulation in barter_to_money, complexity falls from O(n2) to O(n).

Figure 5

Pricing works! As shown in Figure 5, most of the welfare gains are recovered and the congestion issues are resolved. LLMs may lower the cost of expressing dispersed knowledge, but they don’t remove the need for institutional design to manage externalities. At least in our experimental simulation, the price system remains essential to solve the issue of complexity and congestion.

What did we learn?

If we think about an AI agent economy, we would want to know more about the mechanism that facilitates coordination. First, we have to ask, “If agents lower transaction costs, do markets just happen?”

In a previous post we looked at what would happen if there were a bunch of agents who had to interact with each other to trade, and it turned out that they don’t form markets spontaneously. In fact you have to do a fair amount of work before the agents are ready to interact.

Ok, if markets need scaffolding, what’s the minimal substrate that makes coordination scale? i.e., how will the agents coordinate amongst themselves? Will they be able to develop methods to do so themselves, e.g., through bilateral and multilateral negotiations, or will they need further help. It turns out that no matter how much you want to set things up just so, the agents will still need money and prices to trade efficiently. Even with the lower transaction costs and larger levels of compute, the coincidence-of-wants problem still doesn’t disappear - Hayek remains vindicated.

In this current essay we explore whether LLM agents can make centralised matching more efficient–we should expect marketplace consolidation in categories that were previously too heterogeneous for algorithmic matching, e.g., wedding vendors, specialised consulting, creative services. We showed that in “thin” markets AI agents help facilitate better match quality through centralised mechanisms.

However, if everyone has an AI agent, we still need a pricing mechanism to solve the resulting congestion and complexity problems that arise. Congestion is a serious threat at scale!.

So what is the broader take away from this essay, from the whole series of essays? For us it’s that AI agents work remarkably well when institutional design facilitates the interactions and transactions. Since direct instruction for every eventuality is impossible, the only way to make the AI agents behave at scale is to design the right scaffolding to facilitate coordination and exchange. This involves the creation of markets, and yes, money! If we can learn to design the “institutions” within which the agents operate, then we can help have them do far more complex tasks that we want. Autonomy, that’s the true prize!

Appendix: More about the design

Warning: wonky.

We constructed a simulated marketplace where customers seek service providers (contractors) across task categories that vary in how difficult preferences are to articulate. Each customer is seeded with true preferences represented as a 6-dimensional vector of weights (summing to 1) over provider attributes. A match is formed when both sides’ true values clear a threshold.

“Easy” categories include things like TV mounting or furniture assembly; preferences in these categories can be mapped cleanly onto standard form fields such as price, availability, and distance. “Hard” categories, such as ability to repair a historic staircase or a complicated asbestos remediation with specific guidelines, involve preferences that are more difficult to elicit using standardised questionnaires. We then see whether the ROI threshold changes based on how well the models can “elicit the true preferences” of the underlying actors.

The experimental intervention targets the preference-inference pipeline: how customer preferences get translated into data the platform can act on. The experiment varies the intake method (standard structured forms versus free-text descriptions parsed by an LLM) crossed with the matching mechanism (decentralised search where customers browse and choose, versus centralised assignment where the platform matches algorithmically). Match quality is computed as the dot product of the customer’s true preference weights and the matched provider’s attributes, minus any search costs incurred. All of this is summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure A1: Experimental Design

“If everyone has an AI agent, it’s almost like nobody does” is a killer line. Thanks for a very clarifying piece.

inbox flooding is inevitable for everyone in an LLM world. going to need prices for communication - wrote about this in 2023 - https://sergey.substack.com/p/crypto-mail