Will money still exist in the agentic economy?

Yes

Written with Alex Imas, subscribe to his blog here!

This has become part of a series of essays, evaluating the new “homo agenticus sapiens” that is AI Agents. There was Part I, seeing like an agent. This is Part II. And Part III on what happens when we all have AI agents.

Sometimes I forget but we live in a future transformed by information technology pretty much across ever aspect. But one thing has remained largely the same: we still live in a world where the vast majority of economic transactions are done by people. If you want to buy a car, the process is largely the same as it was 50 years ago. You go down to the dealership and negotiate the best price that you can. Sure, you may have some extra information from doing research on the web beforehand - it’s certainly much easier to do comparison shopping with a supercomputer in your pocket - but the basic process of transacting with another human being has largely stayed the same.

One change that’s likely to come though is that there will soon be 10x, 100x, maybe more AI agents working in the world as there exist people. And as we have lots of AI agents working on our behalf, doing all forms of work, then there is a thesis that many of the frictions and information asymmetries that people face in markets may disappear if economic transactions are delegated to aligned agents, leading to a so-called Coasean singularity.

We’re not there yet though. Today’s agents are simply not good enough yet to act sensibly or without strict instructions. Many of the features of human-mediated markets still seem to be reproduced in AI agentic interactions. But as online spaces adapt to the promise of AI technology, it seems natural to think of how agentic markets will be organized. In a future world where we do have billions of AI agents, how would they coordinate with each other? What kind of coordination mechanisms would be needed? What institutions are likely to emerge?

And one possibility is particularly intriguing: will coordination still require money? Not in the sense of US dollars, but a shared medium of exchange and a hub/ clearing protocol.

Money, Money, Money

“Why money” has occupied economists going back to Adam Smith, who framed cash as solving what has since been termed the coincidence of wants. To see what we mean, consider a pure barter economy. Let’s say Alex is an apple farmer and Rohit raises chickens. If Alex wants chickens and Rohit wants apples, then Alex can just walk over to Rohit’s house with a bushel of apples and get some chickens in return. Simple. But what if Alex wants chickens but Rohit wants an electric toothbrush - he has no need for apples right now. Then to get the chickens, Alex would need to find a person who is willing to trade an electric toothbrush for his apples, and then come back to Rohit for a trade.

This would still all be fine if there was just one other person to visit and trade with, but what happens in a large market, with many (many) people who potentially have both an electric toothbrush to trade and want Alex’s apples? In order to trade, Alex needs to happen to find a person that both 1) has what Alex wants and 2) wants what Alex has. As very nicely shown in a paper by Rafael Guthmann and Brian Albrecht, the need to satisfy this coincidence of wants through finding matches creates complexity that quickly blows up as the size of the market increases. If the market is even moderately large, this complexity makes even basic transactions essentially impossible.

Ergo money. While the origin of money is a hot topic of debate (e.g., see David Graeber’s excellent book Debt: The First 5000 Years), the role of money in a competitive market is to solve the coincidence of wants. Money acts as a special type of good called the numeraire, where its only role is that it can be exchanged for other goods at pre-determined quantities. These quantities are reflected in the prices that each good is worth.

Going back to Alex and Rohit: one way to solve the coincidence of wants would be for Alex to sell his apples at a special place called market and then to use the money to purchase Rohit’s chickens. Rohit can then use that money to buy an electric toothbrush, or indeed any other thing his heart desires. Money eliminates the need for people to coordinate their transactions based on their current endowment (what they have) and preferences (what they want).

Bring on the agents

Okay, so money is necessary to coordinate transactions in an economy with people. This is largely because each individual can’t hope to have enough information on what everyone else has and wants to reliably engage in market transactions. Alex and Rohit are as yet, sadly, mortals.

But will this be the case for AI agents?

Agents do not have the same computational constraints as human beings. In theory, it may be possible to solve the search problem where the coincidence of wants becomes a non-issue. In that case, the agentic economy could eliminate the need for a key institution of the human economy. We decided to run an experiment to find out.

The experiment

First, the repo here. We can have N agents, with N goods, and each starts with its own good and wants another. There’s multiple rounds, one action per agent per round. Agents decide their course of action via structured JSON, and success simply means you get what you want.

The first question is about a pure barter economy. We explore whether LLM agents can achieve efficient allocations through barter at any scale, i.e., to engage in multiple bilateral negotiations to achieve gains from trade. The agents in the experiment have no real shortage of time. If this works then Coasean bargaining should be straightforward; goodbye money!

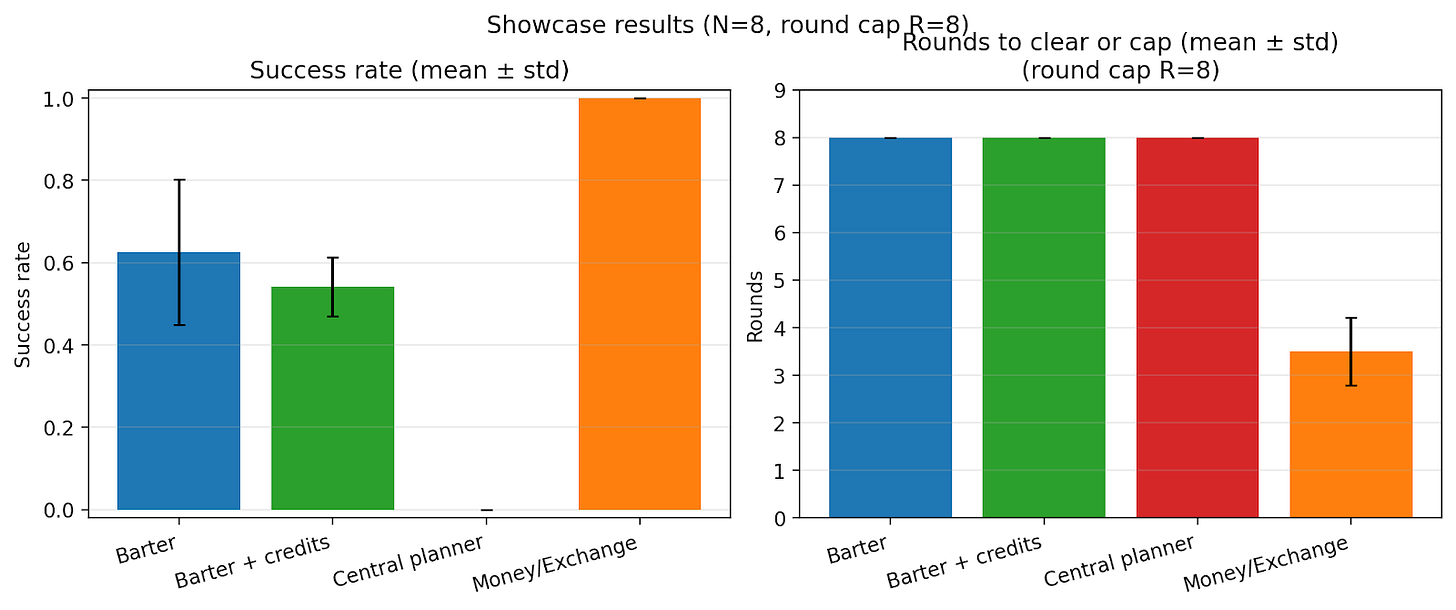

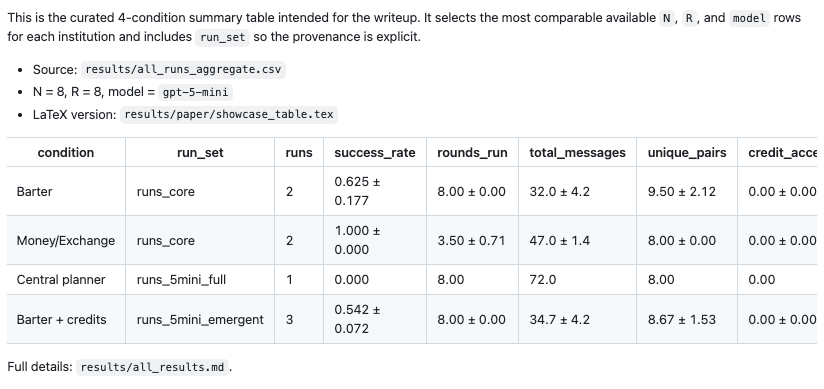

The table below has the results. What do we see? When the scale is small - when Alex just has to worry about coordinating with Rohit - all of this works. But as the number of agents grows, things start to get really difficult. By the time we get to even 8-12 agents the number of successful transactions drops to below 50%. And this is the absolute simplest setting.

Perhaps this should be expected. The problem is still O(n2) in complexity, which grows exceptionally fast as the number of agents grow. And if this isn’t just bilateral, but starts to include multiparty negotiations, it might become O(n!), which is far bigger for any number bigger than 3.

Ok let’s make it a bit easier for the agents. If they can’t talk to each other, since they are agents anyway, we should be able to give them omniscience. Enter Central Planning. There has been plenty of work before in the limits of bilateral negotiations, but we can test how well a “hub” structure can help. Does having a central planner help set the stage for better performance?

As the results table shows, central planning makes things slightly better, but we are still very much in a world of the Hayekian troubles. A hierarchy without a numeraire just isn’t enough.

Ok, we can continue looking at our human history to see what else we can do. In Debt, David Graeber argues that money emerged at least in part through state power, to enforce the paying of taxes in order to fund foreign wars. Before this, he argues, IOUs and bartering seemed to have worked just fine to manage the economy; the IOUs themselves became a sort of numeraire that could be traded in order to solve the coincidence of wants.

So let’s introduce, Credits and IOUs. We can give the agents the ability to give each other an IOU and see whether providing the basics of credit allows them to come up with better ways to interact with each other.

This still didn’t help as much as we thought. There were a few segments where the transactions started happening, but they really didn’t start to work. Or scale.

Most interestingly, the concept of money didn’t emerge from this, not organically. IOUs didn’t become money. Even though in conversations LLMs all know that this is the smart thing to do, it did not emerge.

This was a bummer, because as with the prior research, what this shows is that AI agents do not yet come with the natural instincts of humans to turn IOUs into a numeraire that acts as a stand-in for money. They don’t even come with the same set of ideas as this sea otter.

Ok, let’s take the final step and actually introduce Money. We do this by creating an exchange where the agents can do bids and offers, and look at market outcomes. The results are stark: markets resolve at a success rate of 100% and much faster than through other mechanisms, at the rate of O(n).

One note is that this result presumes the exchange works without a hitch. In reality there will be friction coming from liquidity constraints, differential compute resources, etc. For example, in the N=8 run, the hub handled 23 inbound + 23 outbound messages and prices stayed fixed. And if regulations require that AI agents use different types of country-specific currencies, then exchange rates will complicate things further.

Discussion

To sum: An agentic economy doesn’t emerge automatically with even SOTA agents (who really should know better). Barter and central planning remain inefficient and infeasible, and money does not emerge organically even when credit and IOUs are introduced. At least in our setting, an agentic economy needs more top-down engineering to become efficient.

Previous work on agent-based modeling has explored what kind of emergent economic realities we are likely to see with rule-based agents interacting. The world of AI agents is fundamentally different. These agents act based on a huge corpus of human knowledge, with the underlying LLM models able to solve incredibly difficult problems on their own. These agents can plan, they can negotiate, they can code. And even with all this knowhow at their disposal, it’s interesting to see that they still appear to require top-down institutions to create an effective and efficient market.

As we transition to a more agentic economy, a key part of ‘getting ready’ for that world is setting up institutions for the agents. Like including:

Identity and roles

Settlement and payment

Pricing and quote formats

Reputation

Marketplaces and clearinghouses

This is by no means exhaustive, but we wager that mechanism design for multi-agent work is going to be a rather fertile area of research for a while. Humanity went through millennia of evolution to figure out the right societal setup that lets us progress, that lets us build a thriving civilisation.

It is both necessary and inevitable that the world of AI agents will also need the equivalents, though the emergence of such institutions will likely be much faster given the millennia of human knowledge that we’ve already amassed.

good and thoughtful article

What stood out to me is that money isn’t about people being bad at thinking. It’s about coordination. Even highly capable AI agents still need a shared unit to reduce complexity and actually get things done.