The Slow Apocalypse: When will we run out of kids?

More than you wanted to know about the fertility crisis

I.

I’m not a population expert, but there’s a ticking time bomb. Almost everywhere in the world, pretty much without exception, has lower birth rates than they used to. In fact, most of the world is below replacement (TFR or 2.2 or 2.1, depending on where you live). This is true in the US. In Europe. In Australia. Singapore. Japan. Korea. It’s reducing even in India, South East Asia, Latin America. It’s quite possible that despite the heroic efforts from Africa, we might be at replacement TFR insofar as the world is concerned right now.

And this is likely to continue downwards. In the developed world around 40% of the decline in TFR comes from childlessness, of course this varies by location, and 60% from people having less kids.

Today’s <15 set guarantees rising absolute births through ~2040 even if TFR = 1.7, but the trend is rather clear, just looking at the above numbers. Depending on which numbers you believe people think the global population will peak at like 9-10 Billion in the 2050s, then start dropping.

The reason this is a problem is that people, young working age people, are the lifeblood of the economy. A few repercussions of this population pyramid inversion:

IMF’s medium projection, assuming a Cobb-Douglas world, will cut both the level and growth rate of aggregate GDP - maybe 1% hit to the global GDP growth annually

In OECD the worker:retiree ratio doubles by 2050- this will necessitate a 5% fiscal tightening or debt

With fewer workers and more retirees we will see savings decumulate, because retirees spend more and save less1, and this will hit interest rates

And per Jones idea-production thesis, fewer young workes and researchers mean slower idea generation. OECD estimate is around 0.3% off annual TFP growth.

This is obviously scary for multiple reasons.

Lower economic growth and asset reallocation of that nature brings with it a rather uncomfortable shift in hwo people live

Per capita GDP might be less affected in the aggregate, since capital deepening might offset

And if this continues for a long while, there’s the doomer scenario of “voluntary extinction”

(For example, it makes sense that as population declines we will hit a breaking point for the economy. If demand reduces, which is literally what will happen if there’s less people, then that will affect the price. If the labour growth is negative, then the overall output growth will also be negative. And these fewer working age adults will need to take care of us old fogeys at a much larger proportion when we are older.

OECD will see their pension cashlow turn negative by 20302. Global labour force will peak maybe a decade after that? Long term healthcare bill for the senior citizens will explore another decade after that.

Some worry that this trend is even more apocalyptic. That soon, through the inexorable rules of mathematics, a below replacement fertility rate will result in lesser and lesser people until we’re effectively depopulated.

It’s bad enough that people, smart successful people, are actually contemplating ideas like “let’s not send people to college” in a handmaid’s tale-esque chain of thought. Just like the 1980-2020 saw a demographic dividend, the 2020-2050 will see a demographic drag.

II.

There are lots of reasons people bandy about. Childcare is more and more expensive. Hell, life is more and more expensive. Healthcare is expensive. Housing is expensive. Education is expensive. Opportunity cost of taking your kids strawberry picking on a Sunday is expensive. Etc.

All of which is also true.

The reasons why TFR is trending lower seem stubborn. No matter what we seem to do it doesn’t seem to reverse. But the economist in me looks at this unbounded curve and asks, “where’s the equilibrium”. Or rather, what are the conditions under which we will likely see the TFR tick back up, to 2.1 or 2.2, and get us to a stable population.

From a review that was published on the fertility question (bold mine):

Our read of the evidence leads us to conclude that the decline in fertility across the industrialized world – including both the rise in childlessness and the reduction in completed fertility – is less a reflection of specific economic costs or policies, but rather, a widespread re-prioritization of the role of parenthood in people’s adult lives. It likely reflects a complex combination of factors leading to “shifting priorities” about how people choose to spend their time, money, and energy. Such factors potentially include evolving opportunities and constraints, changing norms and expectations about work, parenting, and gender roles, and the hard-to-quantify influences of social and cultural factors.

So, at a glance, we’ll need four conditions as I see it:

Cost of having kids has to collapse

Work and family stop being competitive

Cultural status has to shift

Women face less risk from having kids

Now, having kids basically is equivalent to spending like $20k a year or something like that for their childhood, if you’re trying for private schools or nannies and vacations and whatnot. U.S. USDA estimate is $310-340 k lifetime for middle class, 0-17. Yes, an undeniably privileged view but that’s the reality for why many are not having kids in the first place. When median cost for raising a couple kids is half a million or more, that shows up!

The first question that gets asked is, can government subsidies help? We can sort of see from the data. Korea, Hungary, France and Singapore already burn 3-6 % of GDP on baby bonuses, tax breaks and housing perks. They buy at most +0.1–0.2 births, sometimes after an initial bump. That’s not a big boost.

Hungary spends ~5 % of its GDP on incentives yet slipped back to a 1.38 TFR once the novelty wore off because status never shifted and the underlying costs stayed high. I’m going to just assume it will at a global or at least a largely regional scale however, because the alternative feels too much like the earth turning into those clubs I never went to when I was in my 20s.

Italy had a universal child allowance in 2022 and had no real impact of lowered TFR.

What about other costs? Housing has to get cheaper, so you can afford to get the 4 bedroom house to raise your little ones. As demand reduces, so should prices. Instructively, Japan hit the “housing turns negative” wall in 1991, house prices dropped 55% in the following 15 years. China, arguably, entered the same zone in 2022. Also, at some point we will surely make it legal to build more things, if only because the richer older building magnates died out and the NIMBY movement gets starved of oxygen. This should help reduce the burden of bringing another child into the world3.

And despite Japan, a $10 k fall in prices lifts fertility for renters by ~2.4%.

As labour even gets more scarce, will this also get looser? I’d imagine so. Full wage parental leave or low work-week hours for parents seem like they will make a difference at the margin. Success stories remain microscopic today. A few French civil-service tracks, some Nordic municipalities. But if we can scale that globally and TFR moves maybe +0.3? Seems plausible.

Third, culture. This is my blind spot. I can’t quite conceive of people who seem to not think of having children as a “good thing”. I’m assured they exist. But despite this if the pronatalist movement can push anything at the margins how can it not come back! Surely the “child-free to save the planet” idiots have to lose status4.

France is the success case here, in a “one eyed man is kind in the land of the blind” sense, because in Europe they have the highest TFR seemingly mostly through culture. And at least anecdotally the French don’t seem to think of having kids as a burden, and are far more in favour of free-range parenting than anywhere else I’ve been. And they added roughly +0.3 to TFR compared to the european average. Seems good!

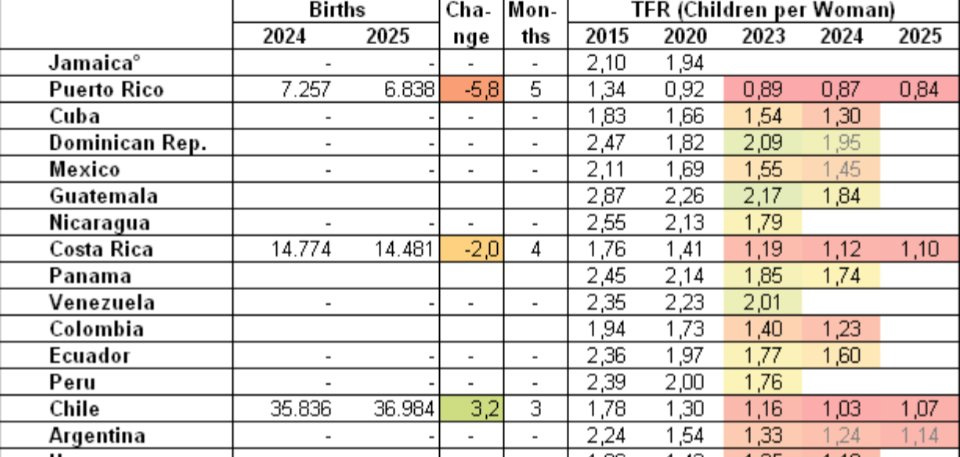

Culture is an incredibly important point, because without it you have to contend with data like this, where Latin American countries fell from above US TFR to below seemingly in less than a decade!

Then there’s the biotech world. Artificial wombs, super cheap IVF, partial ectogenesis, other things that are incredible to think of and difficult to bank on, but plausible.

If the last two exist, that can easily add a +0.5 on the TFR. (Assume some adoption of ectogenesis and some adoption of birth probability along with a general push higher due to culture, 0.5 is feasible. Israel, for instance, did +0.8 pretty much purely through culture.)

To recap, we said 4 factors:

Slash cost of having kids - say +0.3

Make housing (etc) affordable - say +0.2

Cultural pro natalist shift - say +0.2

Biotech - say +0.3

Which means that adding all four can get us back to a 2.1 ish stage. At this point I thought it would be nice to wow you with an equation, so here it is if you’d like to play yourself. It doesn’t matter that much either, but is nice to model things out if you wanted to.

Where C (cost collapse), W (work-family cost détente), S (status flip) and B (biotech). If we use those parameters, then the TFR bottoms out near 1.65 in the early 2040s, and crosses back over in a decade. If you drop the biotech lever to like 0.1, or even delay its launch till 2090, then the year we hit replacement TFR slips to 2060s. (If you use it naively thereafter it also pops back up to 2.6 and stays there but I don’t trust it that much.)

Yeah we’ll need to get enough automation to push the labour productivity up enough to make up for labour shortage. We’ll need real housing construction to drop a lot! And we might need to double again the spending that even the bigger governments are doing to encourage their families to have more kids. All of which seem plausible?

III.

This is all very well to say, how will we fund them? We could break the 4 components down into a few actual policies that I’ve seen floating around. Starting naively:

Kids get a massive allowance - like $1k per child per month.

We also give that to stay at home spouses. We also give the same to like head of family as like a tax credit or something, and double the tax on singles over the age of 25 to compensate.

Make pro natalism cool (i.e., good intentioned govt propaganda, say 2x what we spend on anti-drug PSAs)

Let’s even take away pensions from folks with <2 kids, that’s about 76% of family households and/or about 35% of US adults who are single

Be YIMBY

Doing the maths for the US, that’s basically a cost of around (rounding for ease of math) $1 Trillion for child allowance, $0.5 trillion for spousal and head of family tax allowance, so a total of $1.5 trillion cost.

If you add the new tax you’d get from denying social security to the childless or doubling tax on singles, that’ll get you around $1.2 trillion (roughly).

This means we have to spend around, on average, $300-400 billion annually. Assuming a $150-250k PV net gain from additional child, you’d need to get 2.5-4m extra births a year. For context, US currently is at around 3.6m births a year, so it has to double.

Not to mention, both these numbers will obviously move as people move to a new equilibrium, some people choosing to have kids which increases the spend and decreases the revenues.

You could move the numbers around and somehow make it work on a spreadsheet. You could focus only on marginal births (2nd, 3rd etc). Swap more money for universal pre-k, since that raises payroll and income tax. DC’s universal pre-k led to a 10% jump. Subsidize public IVF (Denmark saw a 14x ROI with this), and go very very deeply YIMBY to lower house prices.

If you did this, we could halve the spend and therefore the PV, while doubling the gains from extra births, meaning the ROI could at least be positive, maybe as much as 2x in the best case scenario.

These are very large, even if not insane numbers, though they sound like it. Social security in the US is around $1.5 trillion a year. Net interest on debt itself is $900 billion. Medicare and defense are also the same. What I found most instructive was to get a sense of proportion, a sense of scale as to what will be required if this were to become an economic necessity. And we can probably do it, which when we’re amidst a sea of people discussing Handmaid’s Tale policies or talking about the destruction of the human race, is good to know!

As the retiree share swells and prime-age savers shrink, the demand for short-duration assets rises just when governments must lengthen debt to cover swollen pension and health bills. Labour markets tighten, pushing wages and headline inflation up; term premia widen because retirees dump equities and long bonds while treasuries sell more of the latter to finance deficits. The net effect is persistent, mild inflation and a steeper yield curve, with risk-asset valuations pressured by slower growth and accelerating dissaving.

More workers didn't translate into more output because the effective labour input and its productivity both deteriorated. OECD annual hours worked are down a tenth since 1980, capital deepening flatlined after 2008, and total-factor productivity growth has halved relative to the 1990s.

So it’s about the fact that labour to raise kids is scarce, or expensive. Which should mean we see many dual income households become single income households when the single income is large enough? I don’t know if this is a widespread trend, but there at least anecdotally seems to be some notion of “enough” and beyond that you can optimise other variables. It’s not like we even need to do that much housework anymore!

Someone once asked me whether I always knew I wanted kids. To me the question didn’t make sense, it wasn’t a question I had ever considered. It wasn’t a spreadsheet question, to tally up the pros and cons of having kids - do I value the fifteen utilons I get from being able to hop off to Kenya when I wanted to against the ten I get from hugging my two year old when he asks me for one? Are these even commensurable?

People make the mistake of thinking of having kids as a utilitarian calculus. It’s not. It’s a stage of life. It is unfiltered joy, ask a parent they’ll tell you. Its not Stockholm syndrome, I remember the life before. It was fine. But while it had plenty of diversions and even more freedom, I used it so little. Your instagram posts about going to Maldives will not give you succour in a year or ten, but kids will. Sometimes you can’t know what you’re missing until you try it.

The day I had my first son I told my wife that my world had expanded. That expansion is not something I can plug into a Benthamite equation. Maybe a being smarter than me will be able to, but until then, if nothing else believe in the fact that we have evolved to have kids, to love them, be loved by them, and it is a joy at which one should leap joyously, not with trepidation at the fact that you do not have a perfect model of what life would be like afterwards.

Excellent article. Perhaps I'm being naive, but I don't see anyone mention the (to me) obvious impact of evolutionary selection. At some point, if the "no kids" mentality persists, all you'll have left are the "oh hell yes kids, damn the cost" people (men and most importantly, women). Then the population delta should become positive again. Might take a century or two. Of course the other factors you mention will probably have an impact before the crude instrument of natural selection takes over.

Really enjoyed this piece - but I think you're underestimating culture's impact on fertility rates.

Cross-country comparisons have limited value since you rarely have a proper control group - within-country comparisons are more useful because they at least control for policy differences.

France is a perfect example of this. France's relatively high TFR vs. EU peers masks significant cultural differences within its population (and I don't think its ascribable to policy success).

Muslim immigrants appear to have roughly 2x the fertility rate of native French citizens. According to Pew Research (2017), Muslims comprised 8% of France's population in 2017, but that's now estimated at 13%. A 2019 study found that immigrant mothers in France had a TFR of 2.7 versus 1.7 for native-born mothers. I wouldn't be surprised if this gap has actually widened.

While I'm absolutely in favor of throwing money at this problem (and we're not doing nearly enough as Caplan would agree), we may need to grapple with the fact that fertility decisions are rooted in beliefs and values that can't easily be shifted.