The Ecology of Companies

Does the Island Rule apply to the markets?

Epistemic status: Highly speculative, since companies are obviously not organisms. But the "island rule" in ecology does seem to parallel quite well in business contexts, so this is an exploration.

I

So a couple hundred years ago, Darwin looked at the variety of finches inside Galapagos and this convinced him about the process of evolution by natural selection. But one of the side-discoveries made during that hunt was on how islands have a peculiar feature - it encourages larger animals to become smaller, and smaller animals to become larger. Here are the cutest versions.

A paper exploring this looked at how the body sizes changed over time for mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians.

The slope of the curve here shows how much gigantism was seen (as seen by the left hand side of the graph pointing up) and how much dwarfism was seen by large animals (the right hand side of the graph pointing down).

We found variations in the processes that drove body size evolution in islands for the different taxonomic groups. Shifts in body mass of mammals were mostly explained by island size and spatial isolation, and modulated by climate (mean temperature)

The explanations usually revolve around a combination of three factors:

Reduced risk of predation means smaller animals can now relax and grow bigger

Reduced food sources mean larger animals can now grow small and survive

Change in climate and temperature seasonality causes differentiation in sizes, for instance with large sizes helpful to store energy reserves for longer

Also, for verisimilitude, increased geographic isolation means inward migration is low, reducing species diversity. Naturally we need to use a few simulations to make this web come alive.

But that's for another day. Let's have a look at another, even more interesting outcome from this weird phenomenon. It means that within an island, the animals are more similar in size than they would be in the mainland.

A corollary that emerges from the island rule is that body size converges on islands. Specifically, if insular environments select for intermediate body sizes, closer to the optimal size of the focal clade, then the size spectrum of organisms found on islands should be narrower compared to the mainland

It's interesting. If an ecosystem is somewhat isolated, we have an odd rebalancing of the species within it such that there are no truly giant ones and everyone's kind of "intermediate".

An island of oddities. An island of intermediates.

II

Now, how does this map onto the ecology of the markets?

Well, to start with there's a literature that treats businesses as if they are participants in an evolutionary cycle. James Moore wrote an article about Predators and Prey, and how the competitive pressures in the world seemed analogous to this. Brad DeLong has written about a business ecology where he's looked at the unique growth cycles of business and how they resemble the evolution of an ecosystem.

So let's take it a step further. If the business world somewhat, imperfectly, has the same dynamics that makes it an ecology, then we should see somewhat similar dynamics between different business ecosystems too.

For example, ecosystems that are more like an island, in the sense that they're more insular, should show more similarity in its sizes compared to large, expansive "mainland-like" ecosystems.

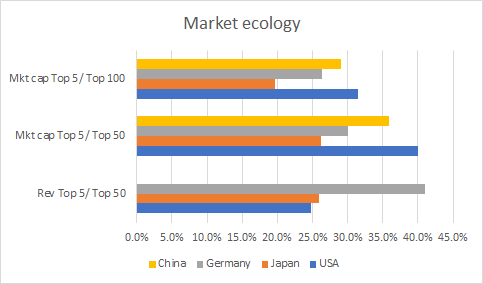

So I looked at Germany, China, Japan, and US, to see what the landscape of companies looked like.

What's fascinating is that if we look at the "insular" island nations, like Japan, they have the lowest disparity between the largest companies and the rest of the distribution.

But there's a kink. If you look at the "largest" in the sense of gaining most revenues, this relationship no longer holds true. It's only in terms of market cap that it really stands out!

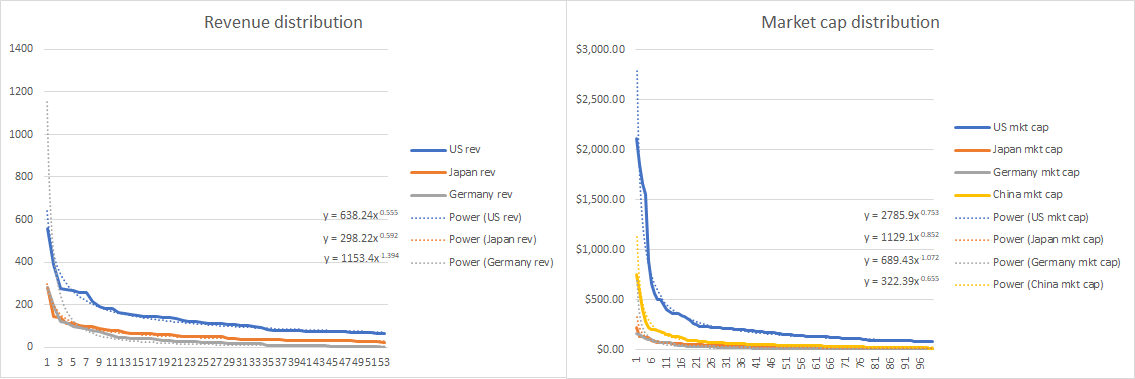

However, when you peer one level below, few interesting things pop out. For one thing, the US market is huge. It dwarfs everything else.

For another, the German market has a couple of outsized mammoths, but then it quickly drops into a sea of similarly sized firms that presumably you couldn’t pick out of a barrel.

(I have a strong hunch that the German data here is particularly biased, as there are a whole bunch of large but private companies in Germany, so if anyone knows a way to fix that let me know!)

III

So, what can we take away from this? For one thing, the Schumpeterian creative destruction takes on a new meaning, when applied at an ecological level. Market expansion leads to giants and minnows, while an island mentality brings equality with minimal variance. Giant markets help bring more innovation in many ways, whereas the island markets bring more stability.

When we look at the largest ecosystems, they are characterised by stasis and then sudden shifts because of an external circumstance, a change in the ecosystem creating a new niche. In an island it’s more filled, and it’s usually the introduction of a new predator that changes the dynamics. Stretching the metaphor, we have technological shifts or cultural changes that push the bigger markets, while the island markets shift when a new species enters from the outside.

In the same vein, unleashing a new breakthrough innovation clearly requires a shift in the ecosystem. Now this catastrophe can come from technological shifts (rise of the smartphone, 4G, changing biotech, CRISPR, availability of new materials) or they can come from business environment shifts (globalisation, contract manufacturing several seas away) or they can come from regulatory changes (anti trust). These are all ways in which we regularly see the business world go topsy turvy and a new paradigm emerge and a new suite of kings and queens emerge.

However the parallel potentially also goes beyond the mere existence. It also tells us that the absence of one of these ecosystem wide shifts, internal or external, results in a more static environment. Over time it ossifies into a structure that can potentially endure for long periods of time without meaningful change.

The fact that today’s world is much closer together in terms of information exchange compared to before also means that the markets are no longer so isolated. It’s as if geology moved back and we’re bringing our continents together to form Pangea again. This means a massive shift in markets, a move towards global giants almost everywhere, and a reduction in the medium-sized mittelstands that could form part of a previously strong economy.

When we are talking about the ecological balance that might be fine, because it gives us millions of years to evolve. But when it comes to change-hungry and progress-minded folk like most of modern humanity, this increased market size means increased polarisation. Understanding the ecosystem we play in changes the way we should see the economy, as is the fact that we’ll have to make the world a tad smaller were we to encourage a different group of species to form!

PS: The papers on ecology make fascinating reading. A few other interesting parallels to be explored in later essays:

Evolutionary rates are much larger in smaller ecosystems, does this mean that a smaller arena is better to spark higher rates of evolution, i.e., startups? We see it in Tel Aviv and the Nordics but Silicon Valley is a rather big exception?

Evolutionary rates do tend to decrease over time as the dynamism of the ecosystem decreases, and the evolutionary niches are filled, until a new cataclysm throws everything up in the air. Is that equivalent to a new technological stagnation?

The actual biodiversity changes based on island isolation, how does this show up in the business context? Could that be the Galapagos effect, for instance in Japanese tech?

Plants are non-migratory and therefore evolve differently, but also seem to obey the island rule. What's the equivalent? Perhaps it's the highly regulated utilities or government depts?