Symposium: The unique uselessness of business advice

Can you learn to invest well, sovereign wealth funds are confused, coffeehouses in the 17th century driving innovation, and labour strikes

Another edition to kick off the weekend.

1/ The magical quest to learn investing

I’ve spent most of my adult life amongst business advice. First with investments, when I ran a hedge fund and tried to learn about investing in the public market. Then with advising corporates and trying to help figure out what they ought to do. And later still then, in venture capital,

All these pieces of advice contain a grain of truth.

Sophie’s post goes from the Graham and Buffett school of value investing to tech-enabled algorithmic trading of RenTech, to macro investing like Tiger to the big picture theories of Dalio to the whole world of private markets where there are thousands of opinions on the best ways to find unicorns.

There’s still an infinite amount of information out there but you’ve at least begun to develop your own worldview. You’ve probably either convinced yourself you could develop a consistent edge and that you love the game, or you’ve become jaded and red-pilled and commit to only dollar cost averaging into index funds.

It’s not just finance. Every area of life seems to be like this.

Like, a friend of mine joined a [TechCo] as a product manager several years ago. And I used to joke that he basically was a consultant to the company’s engineers and their sales people.

But product management is also incredibly important. It is critical to making the thing that gets used by all your users after all. And if you look at the world of product management, it too has its types of advice which all seem very good until you look closely.

Talk to your users, prioritise ruthlessly, start with “why” and not requirements, use data, be fast with a bias for action, coordinate the technologists with the business people. These are all true, but these are all inadequate. Even if you go a level down into the pure action oriented advice, it still is equivalent to building user personas, doing customer interviews, prototyping concepts and running A/B tests, using frameworks like JTBD, building and owning a roadmap, etc.

Career coaching is similar. A wide variety of advice that spans the entire spectrum, which at the end makes much of the advice less useful and less worthwhile.

And Venture Capital? Something I have experience with and have talked about? Well, there are as many good funds as there are ways to invest. Those who focus only on the entrepreneurs, those who do extensive analyses, those who do market analyses and create theses and spearfish, those who let the “best” opportunities come to them, and so on and on and on.

There is no advice that would suit a new investor or teach them what they ought to do in any situation. There’s just trial by fire.

I call this phrase the “experiential epiphany”. It’s like deja vu, but for an idea you once heard and now it makes sense.

Now, some of it is because at the highest level advice kind of becomes pretty generic. They have to compress an enormous amount of insight and most of it is incredibly situational.

And what’s common amongst most investment decisions or business decisions is that they don’t recur. The situations might look similar but the market isn’t. Or the world changes. And the decisions we make assuming ceteris paribus turns out to be not

How often have you looked back and said “huh, that’s what the cliche actually means”.

That’s this phenomenon.

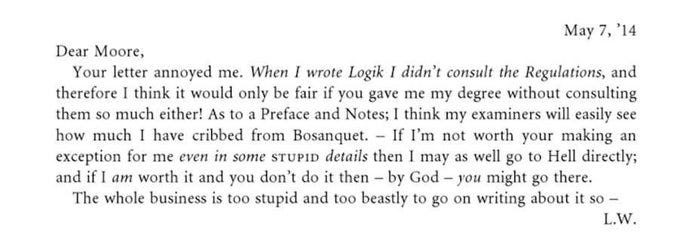

2/ Wittgenstein’s letter

There is little that is not worse today because we have become box tickers in oh so many ways.

3/ Invesco has theories on where to invest

One of the things I like to do is to to read about what asset managers think about the modern crazy macro environment we find ourselves in. From personal experience most of them are basically throwing spaghetti against the wall, moving pieces a little bit back and forth

Over the course of 2022, investors continued to extend their investment time horizons resulting in the sixth consecutive annual increase reported through this study. Sovereign wealth funds reported an average investment horizon of 11.3 years, versus the 10.7 years reported in 2022.

Allocations themselves are hard, with increasing weighting to fixed income and private equity, but they all feel like minor edits at the end of the day. The increase in investment time horizons though feel like playing for time to figure out what to change.

The fact that there is no single easy thesis feels a defining characteristic of the modern environment. Unless for AI I guess. Though nobody knows how to invest in that either, unless it’s to buy Nvidia at 30x sales or load up on big tech.

4/ Third spaces to create communities and hold debates have been around forever

In the 17th and 18th century, there began a coffee drinking scene in London, bringing with it an incredible scene of intellectual debates and spun off innovation. Soon London was only second to Constantinople in number of coffeehouses!

London's coffee craze began in 1652 when Pasqua Rosée, the Greek servant of a coffee-loving British Levant merchant, opened London’s first coffeehouse (or rather, coffee shack) against the stone wall of St Michael’s churchyard in a labyrinth of alleys off Cornhill. Coffee was a smash hit; within a couple of years, Pasqua was selling over 600 dishes of coffee a day to the horror of the local tavern keepers. For anyone who’s ever tried seventeenth-century style coffee, this can come as something of a shock — unless, that is, you like your brew “black as hell, strong as death, sweet as love”,

Some of it was because London’s water was basically not drinkable, and the other alternative was drinking watered down beer.

And it worked! It produced banks, insurance companies, global trade. London became a powerhouse. I’m not saying it’s only the caffeine that helped, but the fact that we started to have third places where people spent time can’t be underestimated. In many ways that’s what we still want.

it soon grew into a forum for literary debate where the stars of literary London — Addison, Steele, Pope, Swift, Arbuthnot and others — would assemble each evening, casting their superb literary judgements

We think about the existence of substack or twitter or threads as these places, and argue about the world where this ceases to be, it’s as if we can’t really imagine a scenario where we don’t have a place to meet people and conduct conversations. All the while when it started centuries ago (millennia if you count Greece, and you should).

The most interesting bit though is this. When we argue the $8 fee for Twitter, we had Penny Universities as cafes, where there was a price to get a coffee and enter discussion.

Traditionally, informed political debate had been the preserve of the social elite. But in the coffeehouse it was anyone’s business — that is, anyone who could afford the measly one-penny entrance fee. For the poor and those living on subsistence wages, they were out of reach. But they were affordable for anyone with surplus wealth — the 35 to 40 per cent of London’s 287,500-strong male population who qualified as ‘middle class’ in 1700

Anything that brings together people to have free flowing conversations in a variety of topics, with cafes specialising as such.

In Hollywood the writers are striking. And now performers are striking too. In the UK the public school teachers have been striking. And now the junior doctors, while senior doctors are picking up the slack. This favour will get returned as the senior doctors go on strike a bit later. The nurses, who are likely around on either side, are also on strike. Over in France, well anyway.

All of which are following a similar script. Labour doesn’t get paid enough, especially these days with the prices going higher. Collective bargaining is basically nonexistent. And then you have folks like Bob Iger from Disney earning $27 million minimum a year telling the writers they really shouldn’t be greedy.

Anyway the thesis is that the supply/ demand logic is inexorable. The logic goes we can’t get another Bob Iger but we can get plenty writers and performers. Which is true but feels incomplete.

Its not that we don’t have many Igers. It’s that we can’t risk trying out too many Igers. The risk of a bad Iger killing Disney is much higher than just paying him his millions.

Well, I don’t know if it is much higher, but it’s certainly thought of as much higher. Feels like something we ought to admit, that being risk-averse creates artificial scarcity.

Previously published: As the world looks at more options to enable creators to get paid, like Twitter starting to pay bigger influencers a share of the ad revenue they create, it’s useful to think about how much this needs to scale before it becomes a large enough payout for most people!

The Creator Economy Needs Fatter Tails

I There is an explosion of belief in the power of creator capitalism that's floating around the tech and VC circles. Clubhouse is supposedly becoming the next big social platform. Patreon is raising capital at $4B valuation. Sahil from Gumroad is one of the most sought after angels for his creator led platform. a16z has talked about the

As always, please treat this as an open thread! Do share whatever you’ve found interesting lately or been thinking about, or ask any questions you might have!

Not sure that the third space metaphor works with the 17th C coffeehouse because the distinction between the two spheres of home and work were not as marked in the same way as they are today. People would work in their homes, live with their workmates, socialize on the street, or in church graveyards, or in pubs etc.

Why does this matter? The coffeehouse wasn't distinctive because it offered a unique place outside of work and home. There were lots of weird social spaces outside of the work and home. But it was special. Why?

We can identify a few things that were new about the London coffeehouse:

1) Drugs. The most obvious was that the coffeehouse served coffee, and people hanging out drinking coffee talk about different things in different ways than people hanging out drinking wine. This was explicitly commented on at the time. Hey, one over caffeinated letter writer said, we used to hang out in the tavern and drink beer and we'd only be able to talk for an hour before we'd get silly. Now we can drink coffee and stay up ALL NIGHT LONG. And this shouldn't be discounted at all.

2) Diversity. Because the coffeehouse was new and people didn't know what to make of it, it attracted a wide variety of people--of men, usually--of different backgrounds and interests who used the coffeehouse for different purposes. At Garraways, you could have an argument about politics, get drunk, or watch the dissection of a dolphin. All in the same place. This was really important, especially at a time when politics and creed were incredibly marked and often led to bloodshed--remember the first coffeehouses started during a period of intense civil war and social dislocation.

3) Information. This is the Penny University aspect. The coffeehouse was often an information clearinghouse. It had newspapers, was a place to send and receive mail, to talk gossip. Over time these solidified: there were places where the maritime insurance people hung out at and these became e.g. Lloyds of London.

Finally. When we're trying to unspool what made the coffeehouse important, we also have to deal with another factor: it declined. Nobody knows when exactly--maybe in the 1720s? and nobody knows why.

But it probably has to do with the fact that these three new social aspects were somewhat at odds. The diversity of the coffeehouse was incredibly productive, but it was also uncomfortable. People would get into fights, they would misunderstand each other, they would talk about topics they shouldn't. Also, over time, coffeehouses started to specialize more and more--so that patrons could get more specialized information. They specialized so much that many became semi-private--like Lloyd's. And slowly the nexus of social energy shifted from public coffeehouse to private club. Specialization shoved out diversity.

What made the coffeehouse wonderful, then, was that for a brief time--like the great parts of the internet--it was a place that was weird and deep at the same time.

Would love to talk more if this is interesting. Wrote my MA on the coffeehouse and my Ph.D. on the Club. Now at MBB doing the consulting thing.

What a fantastic article, thank you!

You're right: ceteris paribus is a clinical trial to tease out specific influences and relationships. It's not the real world. The assumption that it will carry over perfectly from artificial model environment to messy reality is bizarre.